The silence has descended upon Universal Ostrich Farms, a stark contrast to the hours of gunfire that echoed through the southeastern British Columbia landscape just days before. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency has concluded its intensive operation, a heartbreaking necessity triggered by a devastating outbreak of avian flu.

Three hundred and fourteen magnificent ostriches are gone, their lives extinguished by professional marksmen. The carcasses, along with countless eggs and contaminated materials, now lie buried deep within a B.C. landfill – a somber testament to the swift and merciless nature of the disease.

The farm itself remains locked in quarantine, a perimeter established to contain any lingering traces of the virus. Access is strictly controlled, requiring explicit permission and adherence to stringent biocontainment protocols. Every surface, every corner, holds the potential for unseen danger.

The path forward is meticulously defined. Before the quarantine can be lifted, Universal Ostrich Farms must undergo a rigorous process of cleaning and disinfection, a procedure overseen and approved by the CFIA. This isn’t simply about sanitation; it’s about rebuilding trust and preventing future outbreaks.

A period of fallow ground may follow, a time of watchful waiting under the agency’s continued scrutiny. This allows for complete assurance that the virus has been eradicated, and the land is safe once more. The farm’s owners have received detailed documentation outlining these crucial steps.

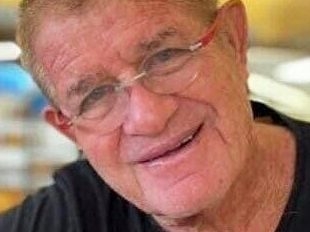

For nearly ten months, the family behind Universal Ostrich Farms fought the cull order, a desperate battle that ultimately reached the Supreme Court of Canada. Their appeal was denied, leaving them to face the agonizing reality of losing their flock. Attempts to reach representatives for comment have, so far, been unsuccessful.

The morning after the cull, Katie Pasitney, daughter of a farm co-owner, described the scene as “inhumane,” the relentless gunfire “overwhelming.” Her words paint a vivid picture of the emotional toll exacted by this difficult decision.

The CFIA maintains that the use of marksmen was the most humane and effective option, a conclusion reached after consulting with experts specializing in ostrich disease management. It was a decision born of necessity, aimed at preventing wider spread of the highly pathogenic virus.

Outside the designated quarantine zones, the agency confirms that personal protective equipment is not required. However, those who ventured into the “hot” zones during the operation were either fully suited up or subjected to thorough disinfection upon exit. Every precaution was taken to minimize risk.

Images from the scene showed workers clad in white protective suits navigating the enclosure, a stark visual reminder of the invisible threat. Pasitney has raised questions about the lack of similar protection for RCMP officers and others stationed just outside the pen.

The question of compensation for the lost flock remains open. Any formal request will be carefully reviewed under the Health of Animals Act and related regulations. The aim of these regulations is to incentivize swift reporting of animal diseases and full cooperation with eradication efforts.

The farm’s story has sparked wider attention, with reports of vandalism at a local CFIA office and drone footage capturing the somber scene above the ostrich pen. It’s a moment that has resonated deeply, marking a turning point for the family and raising important questions about animal welfare and disease control.