The new miniseries, *Death by Lightning*, doesn’t simply recount a historical tragedy; it dissects the American soul. It presents President James Garfield and his assassin, Charles Guiteau, not as opposing forces of good and evil, but as fractured reflections of a nation grappling with its own identity. This isn’t a simplistic tale of a hero felled by a villain, but a haunting exploration of what lies beneath the surface of the American character.

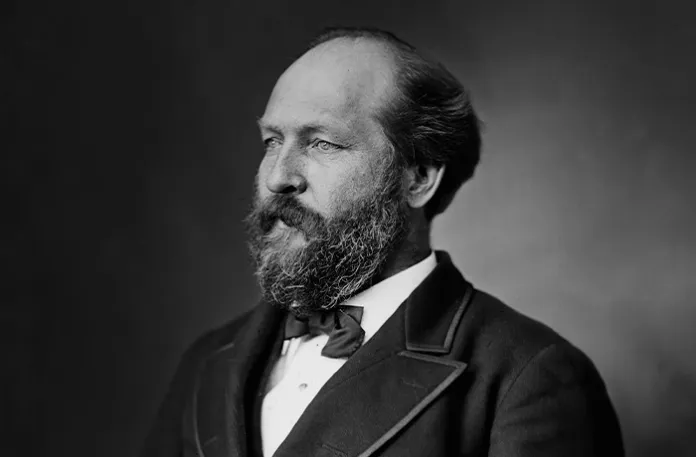

Garfield’s story embodies the American dream – a rise from rural poverty to the highest office in the land. He was a Civil War hero, a champion of equality, and a fighter against corruption. Yet, the series subtly suggests that even the “best” among us carry shadows, and that the narrative of limitless possibility can mask a darker truth. The most unsettling possibility, the one we often avoid confronting, is that senseless violence is woven into the fabric of American life.

The story begins in the summer of 1880, a time of political maneuvering and simmering discontent. Guiteau, a conman and drifter, attempts to charm his way into influence, while Garfield prepares for the Republican convention, burdened by a task he doesn’t desire. The backdrop is a ruthless power struggle between political factions, embodied by the conniving Senator Roscoe Conkling, a master of patronage and control over the nation’s financial lifeline.

Garfield, a man of quiet dignity and reluctant ambition, finds himself swept up in a momentum he barely understands. He initially resists the call to the presidency, even expressing anger at early endorsements. But a captivating speech ignites a firestorm of support, revealing a charisma he hadn’t known he possessed. He’s thrust into the role, a pawn in a deal brokered by others, sensing he’s ill-equipped to navigate the treacherous political landscape.

The series masterfully contrasts Garfield’s reserved idealism with Guiteau’s unsettlingly modern mania. Guiteau, portrayed with unnerving energy, feels like a precursor to contemporary figures fueled by grievance and a desperate need for recognition. Was he a rejected suitor from a peculiar utopian cult? An obsessive fan? Or a harbinger of a darker, more volatile strain of American discontent? The show doesn’t offer easy answers.

What’s truly chilling is the series’ portrayal of a psychopath’s perspective. Guiteau encounters constant rejection, every door slammed in his face – except for one. He believes he *deserves* a place in Garfield’s administration, and when denied, his sense of entitlement spirals into deadly obsession. His plea to Garfield – “Help me succeed like you did” – is a terrifying glimpse into a mind warped by delusion and rage.

The meeting between the two men, though fictionalized, is a pivotal moment. Garfield’s response – a humble acknowledgment of his own limitations and a deferral to divine purpose – feels profoundly out of step with Guiteau’s inflated self-worth. It’s a conversation that highlights the widening chasm between a fading world of faith and honor and a rising tide of self-aggrandizement.

But the story doesn’t end with the assassination. It finds an unexpected resonance in the figure of Chester A. Arthur, Garfield’s vice president. A seemingly unremarkable and dissolute politician, Arthur undergoes a remarkable transformation, becoming a surprisingly effective reformer. His story suggests that even within the most flawed individuals lies the potential for unexpected greatness, and that the American experiment is built on a foundation of constant reinvention.

Ultimately, *Death by Lightning* is a haunting meditation on the complexities of American identity. It’s a story about ambition, disillusionment, and the enduring tension between our ideals and our realities. It’s a reminder that the pursuit of greatness can come at a terrible cost, and that the shadows of our past continue to shape our present.