In the shadowed hollows of Appalachia, the battle against addiction often falls to those already stretched thin: law enforcement. Bre Dolan, a 35-year-old woman from Hardy County, West Virginia, knows this intimately. Growing up, she witnessed firsthand how police officers were frequently the first responders during her father’s struggles with addiction and mental health, men and women she remembers as genuinely caring about their community.

Yet, despite their dedication, Dolan harbors a deep skepticism. She questions whether traditional law enforcement can truly address the agonizing roots of a crisis that has gripped her state for generations. “Most of the busts are addicts,” she observes, her voice laced with frustration. “People who need help, not handcuffs.”

Dolan’s story is a personal one. Her father’s battle mirrored her own, a harrowing descent into addiction she fought her way out of fourteen years ago. Now, she watches with growing dismay as local officials allocate millions of dollars from opioid settlement funds – money intended to heal communities – towards police equipment: Tasers, armored cruisers, and advanced surveillance technology.

Nationwide, a year-long investigation revealed over $61 million in opioid settlement funds were directed towards law enforcement in 2024. While some initiatives, like pairing officers with social workers during overdose calls, garnered support, many experts questioned the wisdom of bolstering police arsenals in a public health crisis.

Over the next two decades, states and localities are poised to receive more than $50 billion from these settlements, funds earmarked to combat addiction. The agreements even included guidelines for responsible spending, a lesson learned from the shortcomings of the 1990s Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement. But significant flexibility remains, and what one person deems a wise investment, another may see as a profound waste.

Dr. Stephen Loyd, an addiction medicine specialist who once battled his own opioid addiction, feels a particular sting. He views some law enforcement expenditures as a betrayal of the sacrifices made to secure these funds. “People died for this money,” he states, his voice heavy with emotion. “Families were shattered. To not use it to build a better system, to prevent future suffering… it’s unconscionable.”

A comprehensive national database, compiled from over 10,500 examples of spending, paints a stark picture. Nearly $2.7 billion was allocated in 2024. The majority – $615 million – went to crucial addiction treatment, $279 million to overdose reversal medications, and $227 million to housing programs. But a disturbing portion found its way to questionable initiatives.

The database revealed expenditures like $12,000 for rifle suppressors in Indiana, $21,000 for Tasers in another Indiana town, and nearly $70,000 in West Virginia for a police officer assigned to a drug task force, complete with new weapons and tinted patrol car windows. Even seemingly innocuous spending, like funding a fishing tournament as a prevention program, raised eyebrows among experts.

Local officials often justify these choices by citing local politics and constituent demands. In Hardy County, Commissioner Steven Schetrom explained that allocating a quarter of their settlement funds to law enforcement simply reflects “how my population would like me to vote.” The pressure to maintain existing services, even in the face of budget cuts, often outweighs the call for innovative, treatment-focused solutions.

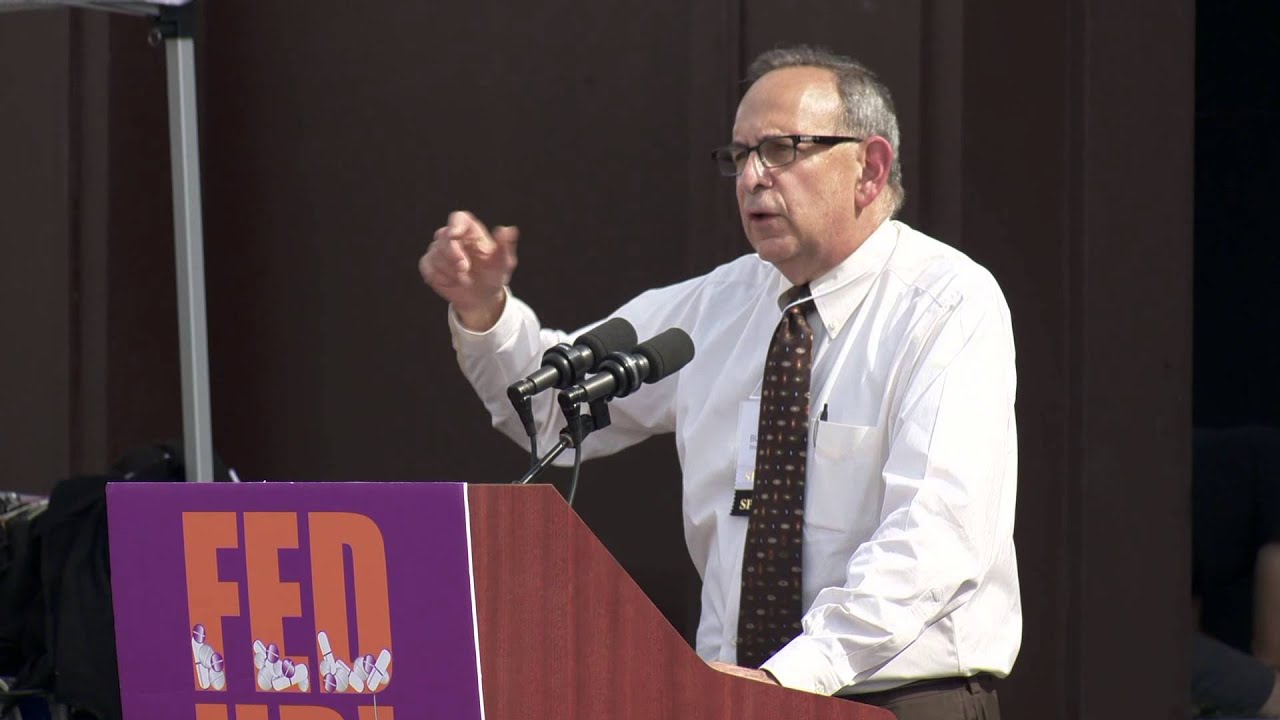

The practice of using settlement funds to offset existing budgets is legal, but widely criticized. Daniel Busch, chair of the FED UP! Coalition, a national advocacy group representing families impacted by addiction, describes it as “painful” and “distressing.” These funds, he emphasizes, represent the tangible cost of lost lives, and diverting them to maintain the status quo feels like a profound betrayal.

However, a shift is beginning. Some states, like Colorado, are actively discouraging the practice of using settlement funds to backfill existing programs. Attorney General Phil Weiser insists, “We have to build on whatever we’re doing because it hasn’t been enough.” Other states are improving transparency by requiring local governments to report their spending, making it harder to conceal questionable allocations.

Jennifer Twyman, a Kentucky advocate who overcame her own opioid misuse, sees the urgency of the situation. “We have people literally dying on our sidewalks,” she says, her voice filled with desperation. To her, any spending that doesn’t directly address the needs of those struggling with addiction is a misdirection of resources, a betrayal of the lives lost.

She remembers the friends she’s lost, the battles they fought, and the potential that was extinguished. “That money could have been me, could have been my life,” she says, a chilling reminder of the human cost behind every dollar spent – or misspent – in this ongoing crisis.