A chilling silence descended over Louisiana as a dangerous threat quietly took hold. While public health officials typically respond swiftly to outbreaks of preventable diseases, a critical delay unfolded during the state’s worst whooping cough epidemic in 35 years.

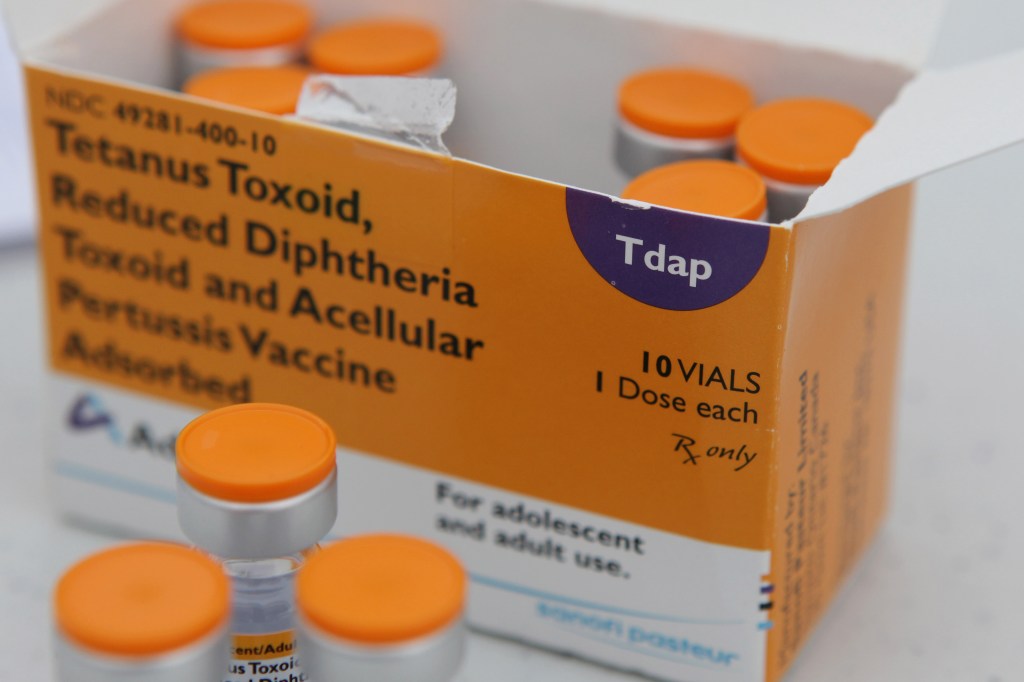

Whooping cough, or pertussis, is a highly contagious respiratory illness, particularly devastating for infants. The disease can trigger violent coughing fits, leading to vomiting, breathing difficulties, and in severe cases, pneumonia, seizures, and even—though rare—death. The vulnerability of newborns is acute, but a protective shield exists: vaccination during pregnancy can transfer immunity to the developing child.

In Baton Rouge, pediatrician resident Madison Flake witnessed the terrifying reality of the outbreak firsthand. She cared for an infant, barely two months old, who required intensive care. “He had these really intense coughing episodes,” Flake recalled, “He would stop breathing for seconds, almost up to a minute.”

By late January, tragedy had already struck twice, with two Louisiana infants succumbing to the disease. Yet, the state’s Department of Health remained largely silent, waiting two full months before posting a single message on social media suggesting residents discuss vaccination with their doctors. A formal health alert to physicians, a press release, or even a press conference were nowhere in sight.

Experts were stunned. Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association, emphasized the urgency typically applied to childhood diseases. “We usually act immediately,” he stated, a veteran of public health leadership in Maryland and Washington, D.C. “These are preventable illnesses and deaths.”

The speed of response is paramount when dealing with infectious diseases, explained Abraar Karan, a Stanford University professor with experience in outbreak management. “Time is, perhaps, one of the most important currencies you have.” A delayed response squanders a crucial window of opportunity to contain the spread and protect the vulnerable.

The situation worsened in February when the state’s health director, Ralph Abraham, issued a memo halting general vaccine promotion and community vaccination events. This decision coincided with the Senate confirmation of Robert F. Kennedy Jr., a prominent anti-vaccine activist, as the new Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Abraham followed up with another memo on the state health department’s website, claiming public health had overstepped with its vaccination recommendations, driven by a “one-size-fits-all collectivist mindset.” He had previously labeled COVID-19 vaccines as “dangerous” and publicly supported Kennedy. Only after a query from a local news station did the department confirm the deaths of the two infants via email.

The silence continued. Over the following month, two more infants were hospitalized with whooping cough, according to internal emails obtained through a public records request. It wasn’t until March, prompted by inquiries from NPR and KFF Health News, that the department posted its first social media messages about the outbreak and offered interviews to other media outlets.

The first official alert to physicians arrived on May 1st—at least three months after the second infant death. A press release followed the next day, and a press conference was held on May 14th. By then, 42 people had been hospitalized, and three out of four hadn’t been fully vaccinated. Over two-thirds of those hospitalized were infants under one year old.

As summer arrived, cases continued to climb, but the state health department remained largely quiet. When contacted for comment in September, a spokesperson offered only a recent post from the state health director stating the department had “consistently reported pertussis cases and provided guidance” for 2025, while also calling the pertussis vaccine “one of the least controversial.” The post notably omitted data for 2024 and 2025 and misdated the infant deaths.

Experts agree the response was a “disaster waiting to happen.” Karan emphasized the need for immediate public alerts following the first infant death, urging a strong message: “Babies are at high risk. They get it from people whose immunity has waned. If you haven’t been vaccinated, get vaccinated. If you have these symptoms, get tested.”

Tragic deaths from preventable diseases, experts say, present an opportunity to educate the public and save lives. Joshua Sharfstein, former Maryland health secretary, noted that two infant deaths should have served as a clear signal of a real threat to children’s health.

The delayed response, Karan warned, likely fueled a more severe outbreak. “What you see after that is a disaster, a massive outbreak, a lot of hospitalizations.” By September 20th, Louisiana had recorded 387 cases of whooping cough in 2025, shattering the previous high of 214 cases in 2013.

Joseph Bocchini, president of the Louisiana chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics, stressed the need for an aggressive and consistent response. “People need to be regularly informed and reminded of what they need to do: get vaccinated, get vaccinated if you’re pregnant, and see a doctor if you have a cough.”

Ultimately, Benjamin of the American Public Health Association, emphasized that the core goal of public health communication is to prevent the next hospitalization or death. “The bottom line is it’s not too late,” he said. “You can still act more aggressively and proactively to address whooping cough.”