Here’s how it works: You shout out “6-7!”

That’s it.

Does that make sense? No? That’s kind of the point.

Classrooms and hallways have been echoing with cries of “6-7” for months. Triggers include hearing the word “six,” hearing the word “seven” or any situation involving numbers. The catchphrase is accompanied by a palms-up gesture that sort of looks like a pantomime of comparing two grapefruits.

“Six-seven” is often shouted in a specific cadence that draws out the phrase’s last syllable (i.e. “six-sev-eeennn”):

-If you’re a boomer, it might sound like a “wolf whistle.”

-If you’re Gen X, it might sound like Rob Schneider saying “Makin’ copies” on SNL.

-If you’re a Millennial, it might sound like Linda on “Bob’s Burgers” saying “All right!”

-If you’re Gen Z or Gen Alpha, you already know how it sounds (and probably already stopped reading).

“Six-seven” is now an IRL phenomenon, but it spread via social media.

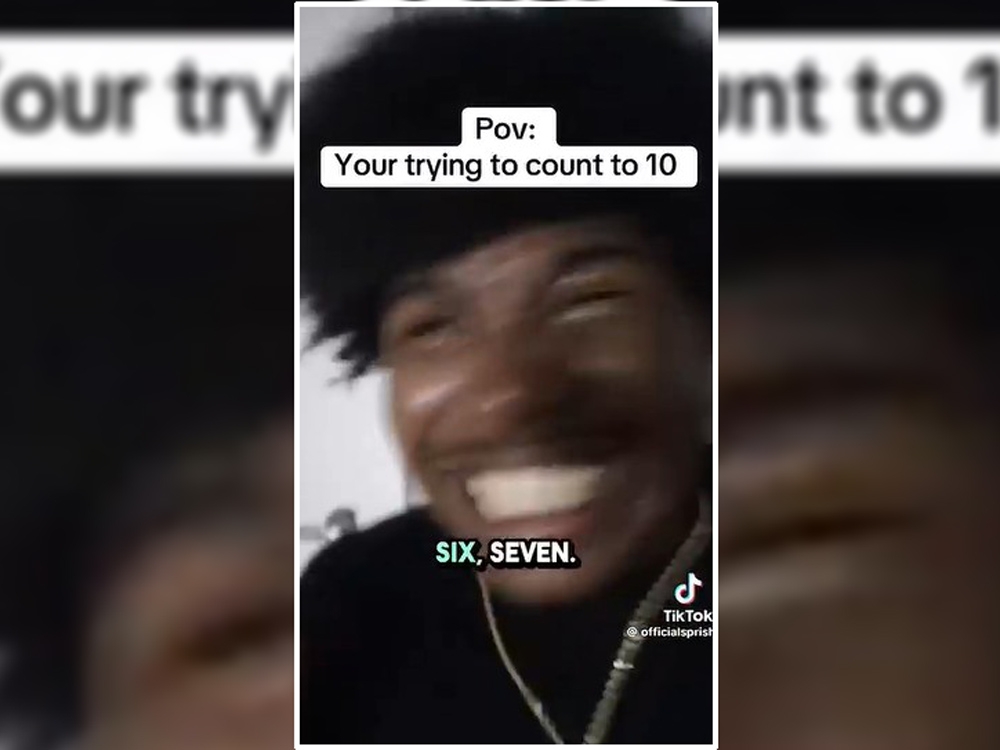

Jayden Tatum, 21, is a senior at Howard University who makes content under the name Sprish. In early September, he made a video about a person who can’t count to 10 without doing the “6-7” thing, inspired by his younger brother. With more than 18.4 million views, it’s his most successful video ever.

“It’s really dumb, but it’s really beautiful because it’s dumb,” Tatum said. And the video is funny because it’s true: “I can’t count or do anything when those numbers come up,” he added.

Aspen Bohlander, 15, estimated that she hears “6-7” around 80 times a day. “It’s more of an ironic thing,” said Bohlander, a sophomore at Oak Park and River Forest High School in Oak Park, Ill. “People are making fun of the fact that it’s not funny.”

“It’s going to die out soon, and there’s no meaning behind it,” Bohlander concluded.

Maybe so, but older people – and the media outlets they pay attention to – have taken notice. The Wall Street Journal reported on how disruptive the trend is for math teachers. Principals are making videos about how to talk to their students about it. Teachers are explaining what it means to parents.

The latter are part of an online cottage industry of adults explaining slang to other adults. As new terms travel further and wider than ever and Gen Alpha non sequiturs become ever more inscrutable, hundreds of slang translation videos have popped up on social media.

Blue Franklin is a creator who makes videos that “translate” slang from Gen Alpha to Gen Z to millennials. Examples include “No cap is no lie is for real” and “Skibidi is chaotic is random.” (Not surprisingly, there are many young commenters telling him he’s gotten something wrong.)

According to Franklin, “6-7 is 21 is 69.” What is 21? An old viral Vine video in which a boy got a math problem wrong. What is 69? Ask Jane Birkin and Serge Gainsbourg.

The origins of ‘6-7’

But back to “6-7.” The meme originated from the song “Doot Doot (6 7)” released by the rapper Skrilla in December 2024. The “6-7” he’s referring to is 67th Street in Philadelphia, a block where a lot of his friends used to live.

Skrilla said he hadn’t realized just how much people were connecting with his track until he left to tour a week ago.

“How they react when I get onstage, when I perform ‘6 7,’ that’s how I know, it’s the energy,” he said. “They’re getting turnt, there’s more people. It’s quadruple the amount it used to be.”

He was speaking from a gas station on his way to Los Angeles. “We just rode by a truck that had ‘6-7’ written on it in dust, in Arizona, all the way out here,” he said, smiling into the sun.

Taylen Kinney, a 17-year-old point guard who plays in the Overtime Elite basketball league, started working “6-7” into a bunch of his social media videos. Now, he sells his own line of “Mr. 67” merch and has created his own brand of “67” canned water.

Perhaps the best-known “6-7” meme is of a 12-year-old named Maverick Trevillian excitedly shouting “6-7” with his friends during a basketball game organized by the internet personality Cam Wilder. With his phone in hand, his oversize gray hoodie and his swooping blond hair – coiffed into what is known as an “ice cream haircut” – Trevillian was a perfect avatar of Gen Alpha giddiness. The video travelled far and wide. He became known as “the 6-7 kid.”

Recently, Trevillian, now 13, went to a carnival near his hometown of Severna Park, Maryland.

“I could only ride one ride because everybody there was crowding me,” he said.

He was having breakfast in the lobby of a hotel in Los Angeles, sitting beside his parents, Jamie Trevillian, 41, and Brandon Trevillian, 44. The family had travelled from their home to attend a basketball tournament played by a variety of internet celebrities.

“Kids are saying ‘6-7’ every second of every day,” the teenager said.

How does that make him feel?

“It makes me sometimes sad and mad,” he said.

“And?” his mother asked.

“And annoyed,” he said.

“And anything other than negative?” she asked.

“And happy,” he said. He forked a blueberry into his mouth. His mother laughed.

Online, fake “6-7 kid” accounts and unsanctioned merch abound. At first, the Trevillians tried to get some of the impostors shut down, but they didn’t have much luck. “Obviously, with branding him specifically we will have his own trademark and his own brand, which is what we’re doing,” said Jamie Trevillian.

Some people started invoking Maverick Trevillian as an example of a “Mason,” a derogatory-ish term for an archetypical mischievous White boy who plays baseball, uploads videos of himself pulling pranks, and latches onto internet trends and lingo. Trevillian had never heard the term until people started calling him “Mason.”

“He became the poster boy because the ‘Mason’ stuff was already kind of going viral before he went viral,” said Henry De Tolla, 22, who makes videos about internet culture under the name H00pify.

For several months, he’s devoted his channel to all things “6-7,” tracking down and interviewing Trevillian and the other people who appeared in the video.

De Tolla also helped popularize “41,” a meme in response to “6-7” inspired by a hip-hop track by Blizzi Boi. He and another streamer made a video doing the “official 41 hand movement” with their palms facing down. It got 5 million views.

Is ‘6-7′ 2025’s ’23 Skiddoo’?

“Usually, by the time newspapers or academics talk about these things they’re already long past their prime,” said Salvatore Attardo, a professor of linguistics at East Texas A&M University. “Memes are fads. They last very little time and then they disappear.”

Attardo has been researching humour in linguistics for the past 40 years. In 2023, he published “Humour 2.0: How the Internet Changed Humour.”

“From one perspective nothing has changed,” Attardo said. “The deep mechanisms of humor – incongruity, resolution, targeting somebody, making fun of somebody – are exactly the same since the Greeks.”

According to Attardo, it’s the format, not the content, that has radically shifted. “You used to read humorous novels that were hundreds of pages long,” he said. “Now, it’s 10-second videos.” Or two-digit numbers.

Attardo acknowledges that Gen Alpha seems particularly enamoured of inscrutable, seemingly nonsensical content. But he cautions against a moral panic about brainrot.

“It is essentially good fun that Gen Alpha is using to create an in-group/out-group division between old fuddy-duddies that are not in on the joke and themselves.”

There’s also historical precedent for a seemingly random number suddenly turning into slang.

The “6-7” trend bears a remarkable similarity to a fad from more than 100 years ago, when trendy young Americans couldn’t stop shouting “23 skiddoo!” at one another.

The “23 skiddoo” fad reached its apex between 1905 and 1906 (five-siiiix!) but lingered for several more decades.

The phrase probably originated from the corner of East 23rd Street and Broadway in New York, where the Flatiron Building’s acute facade could channel gusts of wind that sometimes lifted women’s skirts. When cops would encourage groups of onlookers to disperse, it was known as “giving them the 23 skiddoo.”

But “23 skiddoo” developed multiple meanings. It could mean “time to go,” but it was also used as a cat call, a flirtation, or a catchphrase that inspired advertising slogans, social events, and merchandise like postcards, pins and hats. In one sad case, it was included in a suicide note. Decades later, in the cult “Illuminatus!” novels published in 1975, “23 skiddoo” was repurposed to mean a moment when a pattern or conspiracy reveals itself.

Gen Alpha didn’t invent the practice of adopting a random number as a catch phrase. And it didn’t invent profiteering off a fad.

At this point, “6-7” is ancient. “South Park” did a “6-7” episode last week. Parents are saying “6-7” to their kids to intentionally lean into their own cringe. Teachers are assigning homework inspired by the “6-7” trend. The Washington Post is reporting on it.

But for now, “6-7” and its more obscure descendant “41” live to see another day.

Also, a third number has entered the chat. According to the tireless internet historians at Know Your Meme, 93 became a meme after a TikTok user named ninetythree93._ uploaded a video on Aug. 27 with the caption, “When everybody you know stuck on ’67’ and ’41’ but [you’re] already on 93.”

Less than a month later, on Sept. 26, the same user posted an “official 93 retirement post.”