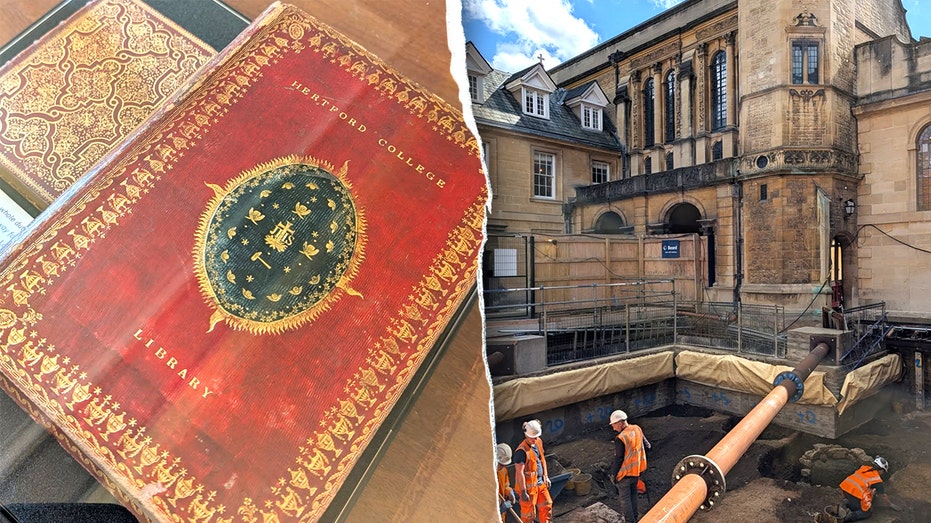

Beneath the manicured lawns of Oxford University, a hidden world has begun to emerge. Recent excavations at Hertford College are rewriting our understanding of student life in the Middle Ages, revealing the foundations of halls lost to time.

Since 2024, archaeologists have been meticulously peeling back layers of history during preparations for a new library. Their work hasn’t just been about laying foundations for the future; it’s been about unearthing the past, specifically the remains of Hart Hall, Black Hall, and Catte Hall – medieval academic centers that thrived long before Hertford College’s 1874 refounding.

The unearthed artifacts span an astonishing period, stretching from the Norman Conquest of 1066 all the way to the 19th century. This remarkable timeline offers a tangible connection to nearly a millennium of learning and daily life within the university’s walls.

Imagine the scholars of centuries past, carefully securing their precious manuscripts. Archaeologists discovered delicate book clasps, the medieval equivalent of a modern bookmark, alongside styli – the tools used to painstakingly write on parchment. These weren’t just objects; they were extensions of the medieval mind.

The remnants of daily life were equally revealing. Rubbish pits, often overlooked in historical accounts, proved to be treasure troves. Animal bones and discarded oyster shells paint a vivid picture of medieval diets, while the discovery of fish remains imported from the River Thames – a 50-mile journey – speaks to a surprisingly sophisticated trade network.

Beyond sustenance, evidence of commerce and personal possessions emerged. Coins and trade tokens hint at economic activity, while combs and clothing buckles offer intimate glimpses into the personal lives of those who once walked these grounds. These weren’t just students; they were people with routines, needs, and belongings.

Leisure wasn’t absent from these halls either. Excavators uncovered clay pipes, drinking vessels, and surprisingly, wooden bowling balls – precursors to modern lawn games. These finds demonstrate that even amidst rigorous study, there was room for recreation and social interaction.

But the most captivating discovery was a perfectly preserved reading stone. Crafted from either rock crystal or glass, this remarkable artifact served as a magnifying lens for medieval manuscripts, allowing scholars to decipher intricate texts. It’s a testament to the dedication to knowledge that permeated these halls.

What makes this reading stone truly special isn’t just its pristine condition, but its continued functionality. It remains a tool for its original purpose, a direct link to the scholars who relied on it centuries ago. The irony of its discovery during the construction of a new library is not lost on researchers.

This year has been particularly fruitful for archaeological discoveries across the United Kingdom. In Scotland, the foundations of a prehistoric village were revealed at a future golf course, offering a glimpse into life long before written records.

Similarly, in the Cotswolds, just west of Oxford, an extensive Roman settlement was unearthed, sparked by the discovery of cavalry swords by a metal detectorist. These finds, alongside the Oxford excavations, underscore the rich tapestry of history woven into the British landscape.

Each artifact, each crumbling wall, is a whisper from the past, offering a more complete and nuanced understanding of those who came before us. The ongoing excavations at Oxford aren’t just uncovering relics; they’re bringing history to life.