Debian is a cornerstone of the Linux world, quietly powering countless servers and embedded systems with its renowned stability. It’s the foundation upon which many other distributions are built, a testament to its reliability and lean design. Yet, for those seeking a polished, immediately accessible desktop experience, Debian often remains overlooked.

This isn’t due to any inherent flaw, but rather a deliberate design choice. Debian delivers software in its purest form, directly from the original developers – Gnome, KDE, and others – without extensive modification. This commitment to upstream projects provides a truly authentic experience, but it also means a less curated, out-of-the-box setup.

Navigating a Debian installation presents a few unique challenges, particularly for newcomers or those accustomed to the simplicity of Ubuntu. The installer demands more detailed information, and the system itself operates with a distinct set of conventions. Even the initial download process requires a degree of Linux familiarity, steering clear of the readily available live systems for those unfamiliar with the process.

Debian’s core philosophy centers on unwavering stability. New versions arrive approximately every two years, and receive three years of support, focusing on security updates rather than constant feature additions. This means the kernel and core software remain largely unchanged for extended periods – a stark contrast to the rapid release cycles of distributions like Arch Linux or even Ubuntu.

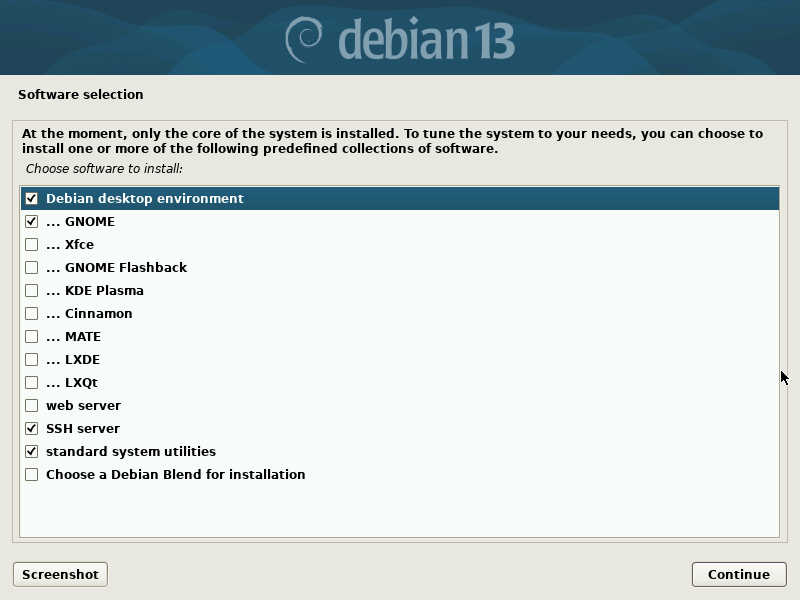

The installation process, while not overly complex, requires attention to detail. Skipping the “Debian desktop environment” option results in a functional, but headless, system. Selecting a desktop environment alone may leave essential software like a web browser or network manager missing. Activating the “Network mirror” option during installation can streamline the process and ensure access to the latest packages.

One of the most significant differences lies in how Debian handles system administration. Unlike Ubuntu’s ubiquitous “sudo,” Debian relies on the traditional “su” command to switch to the root user, whose password is set during installation. While “sudo” can be installed, it’s not the default, reflecting Debian’s conservative approach.

Similarly, essential administrative commands like “usermod” aren’t immediately available in the default system path. Users must specify the full path – “/sbin/usermod” – or modify their PATH variable to include directories like “/usr/sbin” and “/sbin.” These nuances, while easily addressed, can initially frustrate those accustomed to more streamlined systems.

After installation, a common issue arises from the “/etc/apt/sources.list” file, which often includes a line referencing the installation ISO image as a package source. This line must be commented out or deleted to prevent errors during package updates. These seemingly minor details contribute to the initial learning curve for new users.

Debian’s commitment to stability also extends to its package sources. It primarily accepts official DEB repositories, eschewing the use of PPAs (Personal Package Archives) common in Ubuntu. While snaps and flatpaks can be added, they aren’t included by default, maintaining a focus on traditional packaging methods.

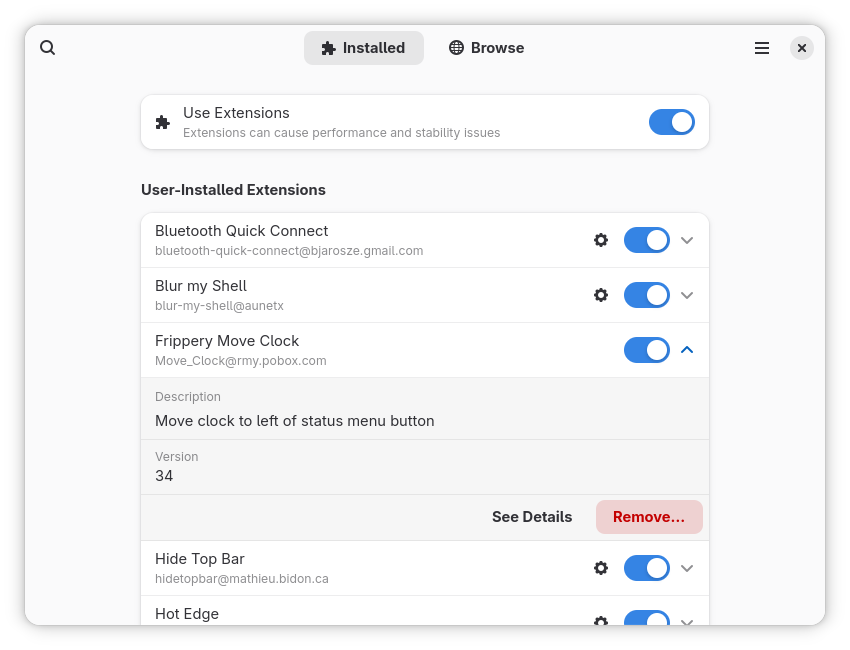

The desktop experience itself is largely unadorned. Debian provides a clean slate, offering a few default wallpapers but leaving customization largely to the user. This is particularly true for desktops like Gnome, where extensions and themes play a significant role in shaping the user interface.

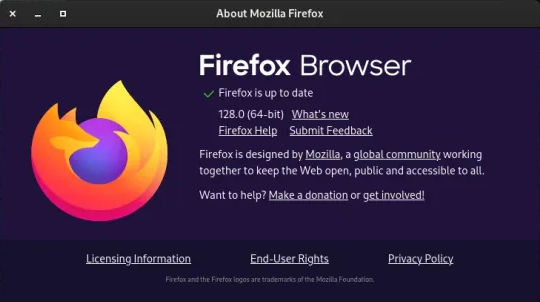

Even the default browser, Firefox, is the Extended Support Release (ESR) version, which receives functional updates only once a year. This reflects Debian’s prioritization of long-term stability over cutting-edge features. However, Debian has become more accommodating regarding proprietary drivers and firmware, now permitting “nonfree” sources by default.

For those seeking a Debian-based experience with a more user-friendly setup, several derivatives offer compelling alternatives. MX Linux, with its XFCE desktop, and Q4OS, featuring KDE, provide a more polished out-of-the-box experience. Linux Mint LMDE, in particular, closely mirrors the simplicity and familiarity of Ubuntu.

Debian thrives in environments where long-term stability is paramount, and hardware changes are infrequent. It’s an ideal choice for systems where consistent performance and reliability outweigh the need for the latest features. For desktop users, a willingness to embrace customization and a tolerance for a slower pace of updates are key to a rewarding experience.