The world of Linux distributions can feel overwhelming. Debian, Arch, Slackware… Ubuntu, Mint, OpenSUSE? Dozens of names swirl, demanding categorization. But beneath the complexity lies a surprisingly navigable landscape, and a few key understandings can serve as powerful guides.

The sheer number of choices is astonishing – around 250 distributions currently available, almost all of them free. But don’t feel pressured to test them all. In fact, a significant 80 to 90 percent can be quickly eliminated, leaving a focused selection of systems tailored to different needs and preferences.

At the heart of every Linux distribution is the Linux kernel. From this foundation, five main “strains” have emerged, forming the basis for the vast majority of available systems. These strains represent distinct approaches to software management, stability, and user experience.

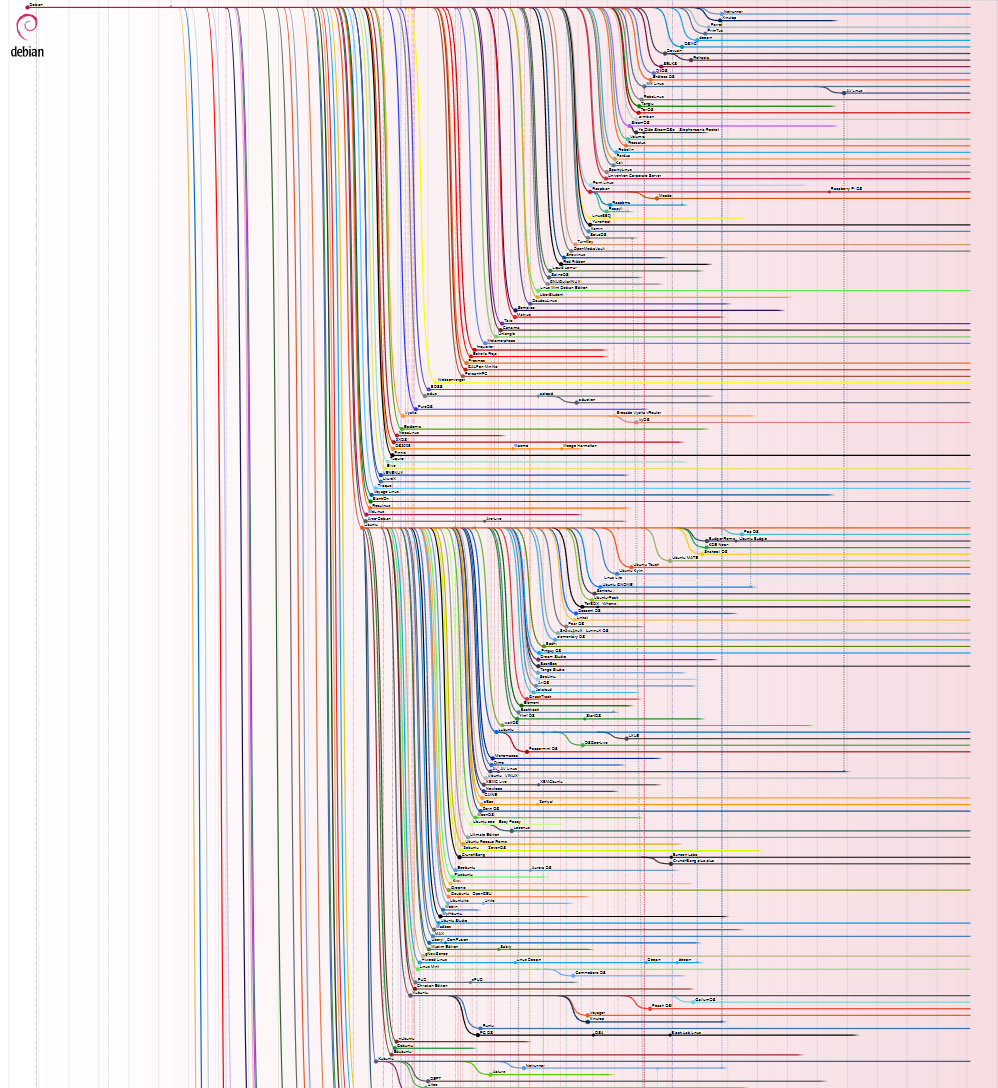

Debian Linux stands as the most influential, spawning approximately 125 active distributions, including popular choices like Debian itself, Raspbian, Knoppix, and the widely-used Ubuntu – along with countless Ubuntu derivatives such as Linux Mint. This dominance stems from Debian’s inherent compactness, flexibility, and renowned stability, coupled with a robust package management system and an enormous software library.

RedHat/Fedora represents the second largest strain, with around 25 active distributions like Fedora and Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL). Arch Linux follows with roughly 20, including Manjaro and Endeavour-OS. Slackware boasts around 10, and Gentoo Linux around eight, including Redcore Linux. Numerous independent distributions, like Solus-OS and Puppy Linux, also exist, alongside mobile systems like Android.

The Debian lineage is truly remarkable, with its derivatives collectively outnumbering all other main Linux strains combined. Many systems, like Linux Mint, Elementary OS, and Zorin OS, subtly conceal their Debian or Ubuntu roots in their branding. This widespread adoption speaks to the strength and adaptability of the Debian foundation.

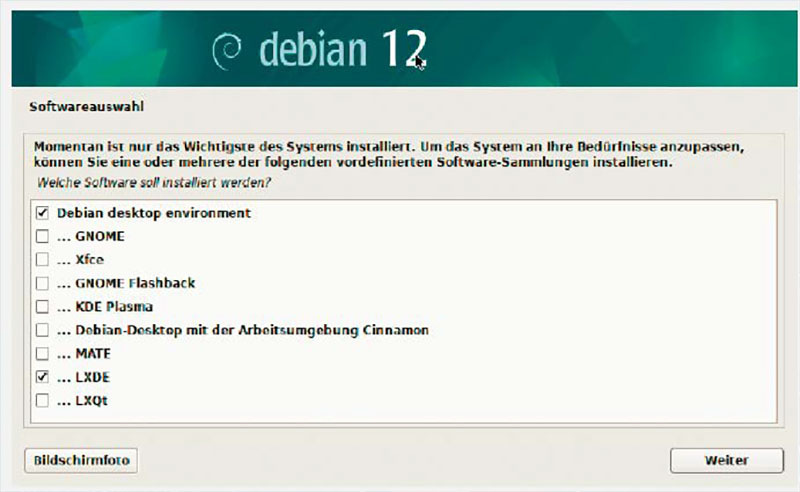

For most users, especially beginners, Debian-based systems like Ubuntu, Mint, and Elementary OS are the most approachable. They offer a comfortable experience and a wealth of available software. The primary potential drawback is that software versions can sometimes lag behind the absolute cutting edge.

Gentoo, Slackware, Red Hat, and Arch-based systems often cater to experienced Linux users and specialized applications. While powerful, they typically require a deeper understanding of system administration. However, Arch Linux offers notable exceptions. Endeavour-OS provides a fast, graphically-installable experience, while Manjaro offers a more user-friendly Arch experience, though neither is ideal for absolute beginners.

Fedora Workstation prioritizes innovation over rock-solid stability, and its installer doesn’t quite match the simplicity of Debian/Ubuntu alternatives. Porteus, a Slackware derivative, excels as a portable, live system for quick browsing. OpenSUSE, while historically linked to Slackware, has evolved into a distinct and reliable distribution, particularly strong in areas like file system innovation.

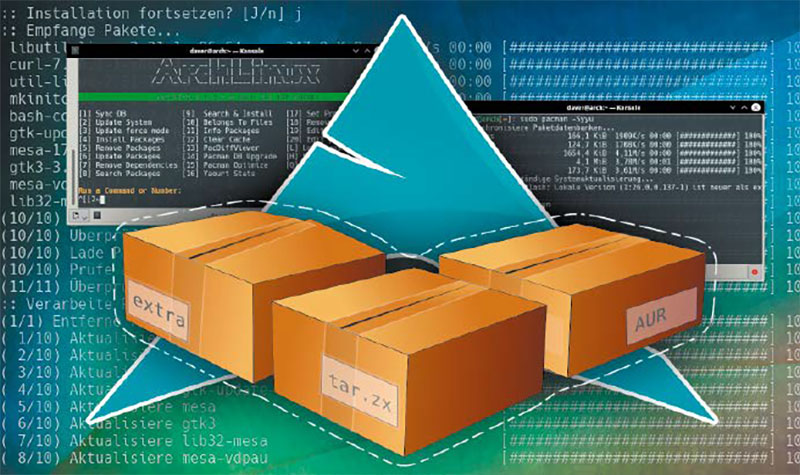

While the specific software you use – VLC, Office suites – may run identically on Debian or Arch, the underlying package formats and tools differ significantly. Once accustomed to the DEB package format (Debian, Ubuntu, Mint) and the ‘apt’ terminal tool, switching to RPM (Slackware, Red Hat, OpenSUSE), Tar.xz (Arch), or Portage (Gentoo) presents a considerable learning curve.

Package management isn’t just a technical detail; it impacts how you install, update, and maintain your system. Graphical software centers are convenient, but often provide limited access to available software. A solid understanding of the underlying terminal package manager is crucial for effective system administration.

Apt, Zypper, and Yum are generally considered relatively straightforward. Pacman (Arch) has a concise syntax, requiring mastery of only a few essential commands. Portage (Gentoo) is notoriously complex, best left to experienced users. Container formats like Snap and Flatpak add another layer of management, potentially increasing system complexity and package sizes.

Avoiding Snaps requires steering clear of official Ubuntu flavors. Flatpak is more flexible, often offered as an option rather than a mandatory component. Distributions like Linux Mint, Elementary OS, and Fedora often include Flatpak support, but don’t force it upon users.

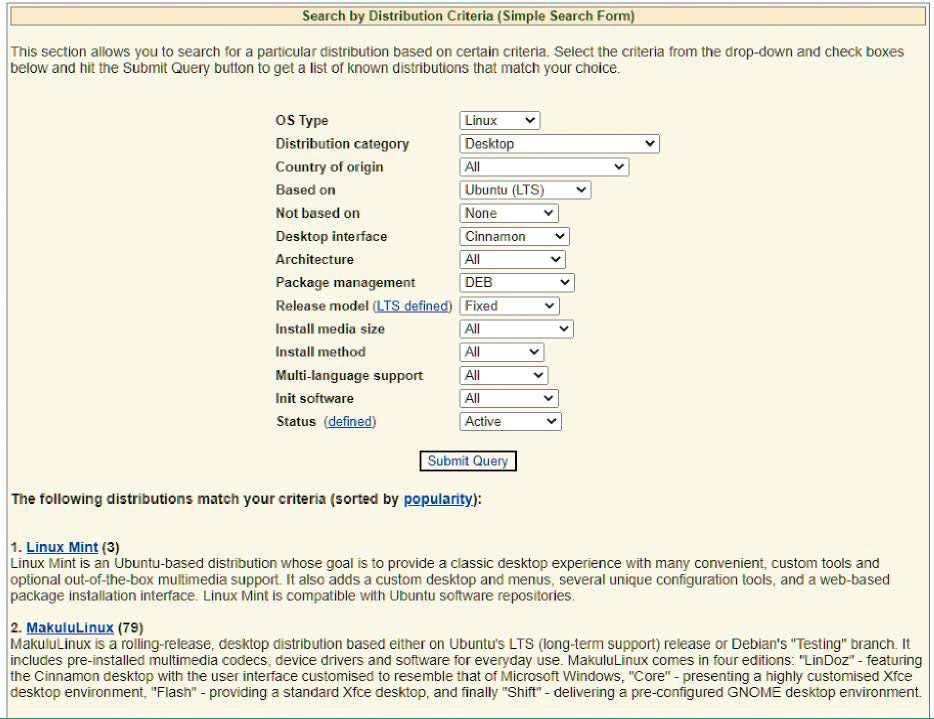

Linux distributions employ different release models, impacting both stability and up-to-dateness. The “Fixed” model, prevalent in Debian, Ubuntu, and Mint, prioritizes stability with infrequent, conservative updates. Long-Term Support (LTS) versions receive periodic point releases for security fixes. This model is ideal for reliability, but software can become relatively outdated.

“Rolling” releases, like those found in Arch-based distributions, continuously update the kernel, drivers, system, and software. This provides the latest features but carries a risk of incompatibility. Rolling releases suit experienced users comfortable with troubleshooting. Semi-rolling releases, like MX Linux, offer a hybrid approach.

The emerging “Immutable” model, exemplified by Fedora Silverblue and Endless OS, separates the core system from user data and applications. Updates are applied without altering the core system, enhancing security. However, this model can be restrictive, limiting software choices and flexibility.

When choosing a distribution, prioritize projects with active development teams and strong community support. Avoid obscure or abandoned projects, which may suffer from language support issues or hidden shortcomings. A robust community ensures ongoing maintenance and problem-solving.

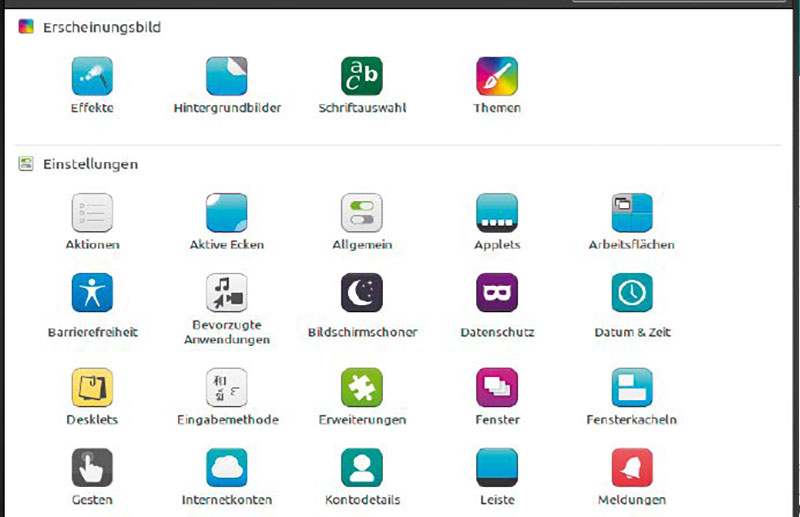

The desktop environment is equally important. While technically interchangeable, the desktop and distribution are often intertwined. Choosing a distribution with a well-integrated desktop environment ensures a smoother, more optimized experience. Distributions like Kubuntu (KDE), Xubuntu (XFCE), and Elementary OS (Pantheon) are specifically designed around their respective desktops.

KDE Plasma offers unparalleled customization and a wealth of features, but can be complex. Cinnamon strikes a balance between functionality and ease of use. GNOME is unconventional but complete, while Mate provides a traditional, familiar interface. XFCE is lightweight and customizable, and LXQT is even more resource-efficient. Pantheon offers a minimalist, macOS-inspired experience.

Ultimately, the best Linux distribution is the one that best suits your individual needs and technical expertise. Careful consideration of these factors will guide you toward a rewarding and empowering Linux experience.