Lauren Hood, 21, armed with a political studies degree, faced a stark reality: four months, fifty applications, two interviews, and a resounding silence. Her experience isn’t unique; it echoes the anxieties of an entire generation confronting a job market that feels increasingly out of reach.

“I didn’t think it would be this challenging,” Hood confessed, recalling the initial optimism after graduation. She remembered applying for a position that seemed tailor-made for her skills, only to learn the company was overwhelmed – over 450 resumes flooded their system, forcing them to close applications early.

Even seemingly accessible jobs – serving tables, working in retail – proved elusive. Each rejection chipped away at her confidence, fostering a sense of futility. The weight of uncertainty settled in, a constant companion in her daily life.

“I feel behind, even though I just graduated,” she admitted, describing a life lacking stability and a predictable schedule. The simple act of getting through each day became a source of stress, a far cry from the future she envisioned.

This disillusionment is widespread. Young Canadians are grappling with a fading belief that hard work guarantees the same opportunities enjoyed by previous generations. They’re facing a landscape of limited opportunities and a soaring cost of living that pushes traditional milestones – like homeownership – further out of reach.

Youth unemployment reached a 15-year high of 14.7% in September, according to Statistics Canada. While numbers improved slightly in the following months, employment levels remained stubbornly low, a persistent shadow over the prospects of young workers.

The decline in stable employment for young people has been a decades-long trend. In 1989, 80% of those aged 15-30 held full-time, permanent positions. By 2019, that figure had dropped to 70%, and by 2024, it had fallen below 60%.

Economic pressures, including U.S. tariffs and trade uncertainty, are contributing to the slowdown in hiring. Economists warn that young and vulnerable workers are often the first to feel the impact when job opportunities dwindle. The market simply wasn’t creating enough positions.

The influx of foreign workers and international students after the pandemic, intended to address labor shortages, inadvertently added to the competition for entry-level roles. While the government has since adjusted immigration policies, the immediate effect is a crowded labor market for young Canadians.

Adding another layer of complexity, artificial intelligence is automating tasks traditionally performed by those seeking their first jobs. This creates a frustrating gap – a lack of entry-level positions needed to gain the experience required for more advanced roles. The question becomes: how do you gain experience when there’s nowhere to start?

Osobe Waberi found herself confronting this challenge and ultimately sought opportunities beyond Canada’s borders. A $500 rent increase in Toronto, a city she loved, proved to be the breaking point. Her full-time job simply couldn’t keep pace with the escalating cost of living.

She relocated to Oman, accepting a two-year permit that offered a chance to accelerate her savings and launch a public relations firm catering to Canadian clients. While homesick for Toronto, she recognized the necessity of prioritizing her financial future.

The dream of homeownership, once a cornerstone of the Canadian experience, feels increasingly unattainable for young people. In 1986, it took five years for a typical 25-34-year-old to save for a 20% down payment. By 2021, that timeline had stretched to 17 years nationally, and a staggering 27 years in Vancouver and Toronto.

While recent market adjustments have slightly shortened that timeline, significant declines in housing prices are still needed to restore the same level of opportunity enjoyed by previous generations. The path to financial security feels steeper and more uncertain.

Experts describe a phenomenon of “economic scarring” resulting from the pandemic. Restrictions on in-person work limited opportunities for young people to build crucial professional networks, hindering their early career development.

However, some suggest this isn’t necessarily a story of lost hope, but rather a shift in timelines. Many young people are pursuing higher education for longer, delaying entry into the workforce and postponing traditional milestones like marriage and homeownership.

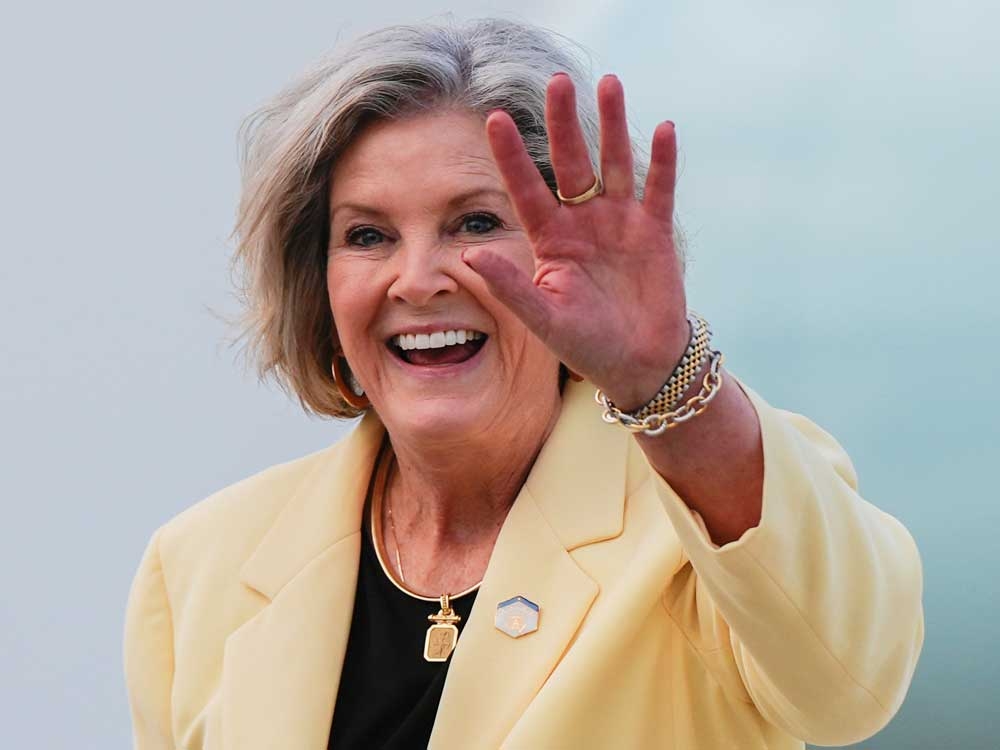

The impact of this challenging job market is felt even within families of economists. Kari Norman, whose own children range in age from 16 to 25, witnessed her university student struggle to find a co-op placement, ultimately taking extra courses to compensate for the lost experience.

The inability to secure work can lead to increased reliance on student debt, a burden that can linger for years after graduation. This cycle of debt and delayed opportunities further exacerbates the challenges faced by young Canadians.

For Lauren Hood, a glimmer of hope emerged a few weeks after sharing her story. She received an on-the-spot job offer at a local retail store. While the position is seasonal, offers no benefits, and doesn’t align with her long-term career goals, it provides a much-needed source of income.

“I am still very grateful to have the chance to get back to work,” she said, a testament to the resilience and determination of a generation navigating an increasingly complex economic landscape.