A quiet battle is brewing beneath the manicured lawns of Toronto’s wealthiest neighbourhoods. It’s a conflict over what lies hidden – vast, subterranean expansions to homes, dubbed “iceberg homes” for the way they stretch downwards, largely unseen. City council is now poised to consider new rules aimed at curbing these increasingly ambitious builds.

For Shannon Rancourt, the issue isn’t abstract. It’s a personal affront to the leafy tranquility of Hoggs Hollow. She witnessed a beloved, mature maple tree felled to make way for a neighbour’s colossal basement – a space boasting a swimming pool and basketball court. “It was like science fiction,” she recalls, stunned by the sheer scale of the plans.

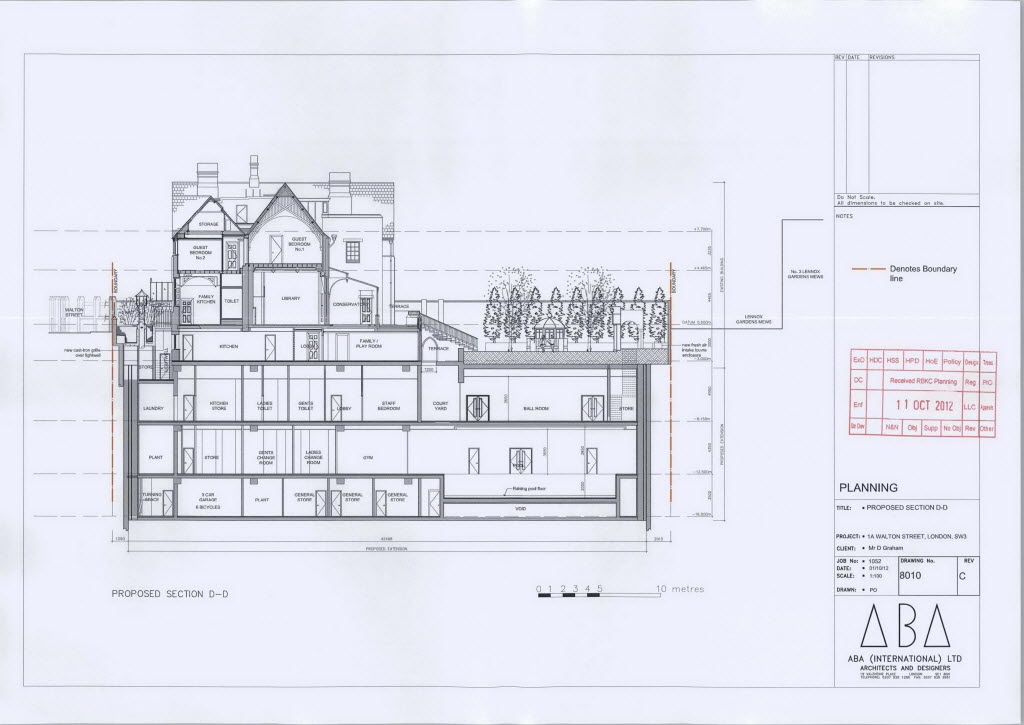

These aren’t simple basement renovations. Architect Richard Wengle, who has worked on several iceberg homes, explains they’re akin to smaller-scale condo developments, requiring complex engineering for digging and water management. The price tag reflects this – investments can easily reach several million dollars, reserved for properties in the city’s most exclusive areas.

But the deeper the dig, the greater the impact. A primary concern is the destruction of tree roots, exacerbating existing drainage problems. Rancourt’s neighbourhood already struggles with regular flooding and a history of landslides, a precarious situation given the area’s proximity to the Don River and its network of underground tributaries.

Wengle argues the criticism is sometimes misplaced. He points out that many downtown properties are entirely paved, offering no absorption for rainwater. Iceberg basements, he suggests, can be more discreet, blending into the landscape in a way that above-ground additions often don’t.

Rancourt vehemently disagrees. She describes one Hoggs Hollow home built into a ravine as appearing as a four-story building from the front, a jarring presence in the neighbourhood. The proposed regulations aren’t just about trees; they’re about preserving the character of Toronto’s communities.

The debate extends beyond aesthetics. Councillor Paula Fletcher has questioned the number of young trees in the city, while Stephen Holyday has raised concerns about the impact on homeowners’ ability to install pools. The sheer complexity of the issue was wryly acknowledged by committee chairman Gord Perks, who quipped, “For anyone who doesn’t understand how interrelated public policy pieces are here at city hall, the item we’re considering is ‘iceberg homes.’”

Councillor Rachel Chernos Lin, representing the affected ward, emphasizes the growing number of these applications and the inadequacy of current bylaws. She points to past rejections at the Ontario Land Tribunal, signaling a growing awareness of the potential risks, particularly regarding mudslides in ravine areas.

Toronto isn’t alone in grappling with this phenomenon. London experienced a similar surge in mega-basements, eventually leading to stricter regulations. While iceberg homes have been quietly appearing in Toronto for over two decades – designed to be, as Wengle puts it, “unseen” – the city is now facing a critical juncture.

The proposed changes represent a shift in priorities, potentially limiting the amount of livable space constructed in Toronto. But Chernos Lin argues this isn’t a paradox. These expansions aren’t about creating more housing; they’re about creating “more house” – a distinction that lies at the heart of this unfolding debate.