A quiet shift is underway in Durham Region, one that’s sparking debate and raising profound questions about the boundaries of community safety and individual freedom. The region has quietly launched a novel program – a “Community-Based Hate Reporting Program” – designed to address discrimination and bigotry, but its very existence is proving controversial.

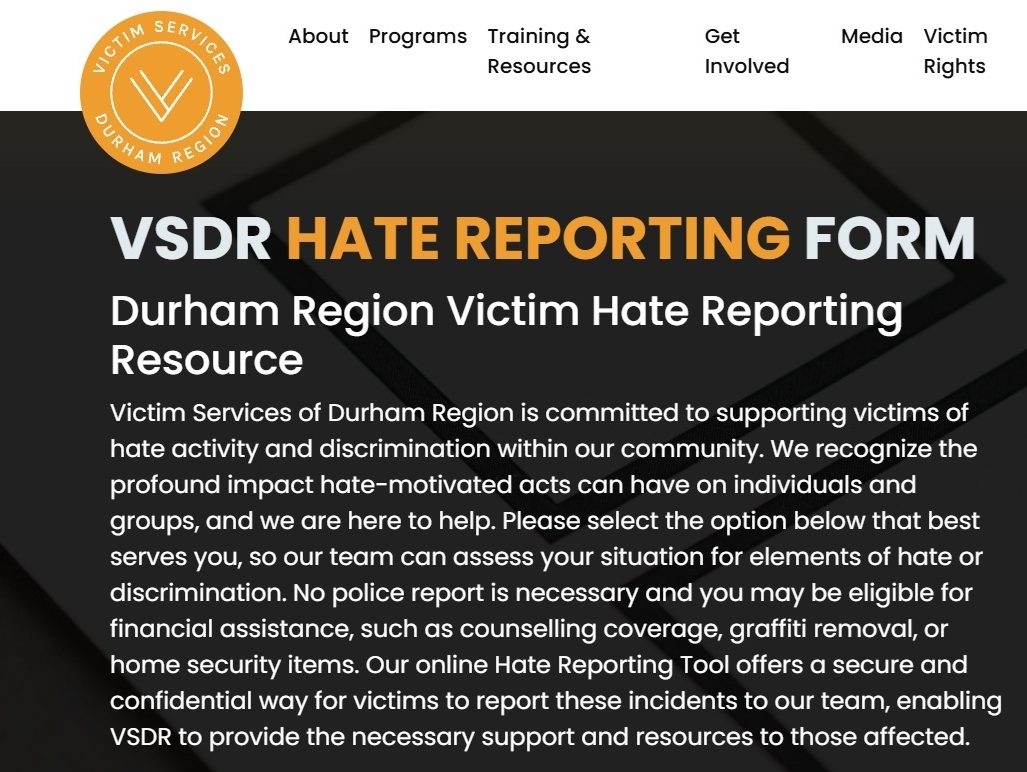

This isn’t a traditional police initiative. There are no badges, no uniforms, and no power of arrest. Instead, it’s a system built on citizen reporting, a platform where individuals can “tell on” one another when they perceive an act of hate, even if it doesn’t rise to the level of a crime. The program promises confidentiality and support for victims, offering an alternative pathway for those hesitant to involve law enforcement.

The core of the program is an online tool, a digital portal for reporting incidents. Victim Services of Durham Region will handle these submissions, providing what’s described as “trauma-informed support.” Funding for this initiative comes from regional taxpayers and provincial government resources, though the exact budget and staffing levels remain undisclosed.

The launch has ignited a critical question: is this a genuine effort to support vulnerable communities, or a concerning step towards a “snitch line”? Regional officials vehemently deny the latter, emphasizing the program’s focus on empowerment and support, not accusation. They argue it fills a gap, assisting those who may not feel comfortable directly approaching the police.

But the distinction feels increasingly blurred. The program acknowledges that the definition of “hate” can be subjective, relying on broad legal definitions encompassing acts motivated by bias or prejudice. This raises the specter of overreach – could a harmless joke, a provocative artistic expression, or even a heated online debate trigger an investigation?

Concerns are mounting that this new entity operates outside the established checks and balances governing law enforcement. Unlike the police, it isn’t bound by the same rigorous standards of evidence or judicial oversight. Who will decide what constitutes “hate,” and what safeguards are in place to prevent the misuse of collected data?

The program’s creators insist it’s about fostering a more inclusive community, a collaborative effort between government, human rights groups, and local organizations. Yet, the potential for chilling effects on free expression is undeniable. Could simply *asking* about the program’s limitations be construed as hateful, prompting an anonymous complaint?

This initiative isn’t simply about reporting incidents; it’s about defining the boundaries of acceptable discourse. It’s a bold experiment, and one that demands careful scrutiny. The residents of Durham Region, and indeed all Canadians, are watching closely to see how this unprecedented program unfolds and what impact it will have on the delicate balance between safety, freedom, and community trust.

The implications extend beyond Durham Region. This program could represent a turning point in how communities address hate, potentially serving as a model – or a cautionary tale – for others across the country.