A go-fast speedboat, bristling with three powerful outboard motors, sliced through the muddy waters of the Orinoco River, deep within Venezuela. On the riverbank, a guerrilla commander stepped ashore, greeted by a wary community. A dozen troops, armed and vigilant, followed close behind.

He approached me, a flicker of amusement in his eyes. “You’re a long way from home,” I remarked, recognizing a Colombian accent. His reply, delivered with a knowing smile, was a fair point – I hailed from London. It was a rare moment of levity in a tense atmosphere, the villagers clearly unsettled by the presence of armed guerrillas.

The commander claimed he was patrolling the river “at the invitation of the president of Venezuela,” tasked with protecting local communities. This was a startling revelation. Historically, Colombian rebel groups sought refuge across the vast, porous border, controlling illicit trade. But this was far inland, over 1,000 kilometers downstream from the frontier. Why such a deep penetration into Venezuela, and why this claim of official sanction?

The answer, revealed in a recent investigation, paints a disturbing picture of a hidden humanitarian crisis unfolding along the Orinoco River. A global scramble for critical metals has ignited a mining boom in ecologically sensitive areas and indigenous territories, unleashing a wave of violence and exploitation.

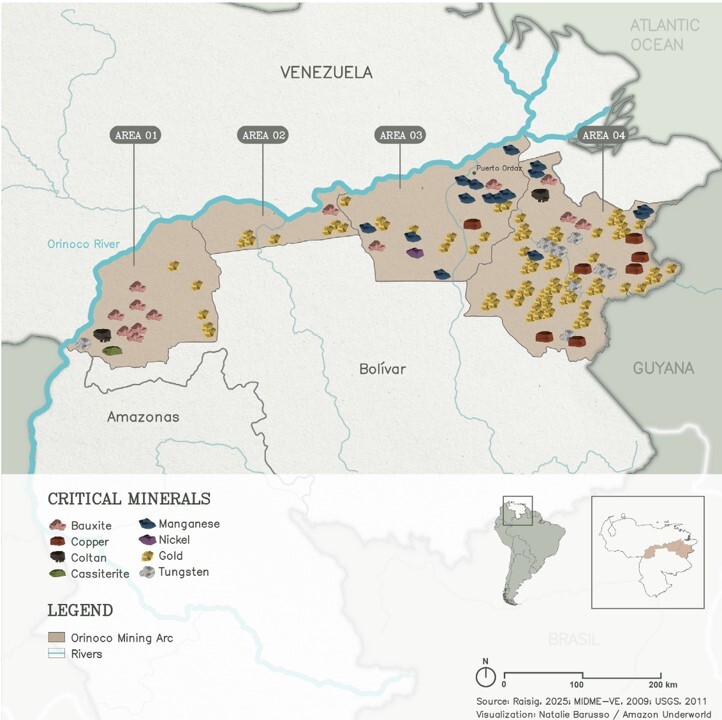

The Guiana Shield, a geological treasure trove over 1.5 billion years old, is rich in tungsten, coltan, nickel, and manganese – minerals vital to modern technology. But instead of responsible development, extraction has fallen into the hands of criminal networks, forging a dangerous alliance of illegal armed groups, corrupt officials, and shadowy companies eager to supply Chinese buyers.

Vulnerable communities are bearing the brunt of this reckless pursuit of profit. Reports detail summary executions, child labor, sexual violence, torture, disappearances, and forced displacement. The crisis is particularly acute on the Venezuelan side of the border, where abuses are rampant and state intervention is virtually nonexistent.

“Mining activities in Venezuela are engulfed in violence and illegality,” explains one investigator. “Human rights violations are far worse than in Colombia or Brazil, as state agencies often turn a blind eye to atrocities committed by armed groups, sometimes even collaborating with them. Mines are controlled with brutal force, and dissent is met with swift and deadly consequences.”

Groups like the ELN have established entire mining villages, complete with infrastructure and services, where miners trade rare earth rocks for goods. The guerrillas either impose taxes or operate the mines directly, while Chinese buyers reportedly arrive by helicopter to oversee operations. Those who challenge the armed groups face imprisonment in makeshift jungle jails, enduring days without food or water.

Witnesses recount chilling stories of locals shot for theft and miners murdered for selling to unauthorized buyers. Traditional ways of life – agriculture, fishing, and hunting – are being abandoned as communities become economically dependent on mining, reliant on costly river transport for basic necessities.

This desperation is exacerbated by the collusion between rebel groups and Venezuelan state forces, who extort miners at military checkpoints or blockade populations, forcing them to work in the mines. “At the entrance to the mines, nobody can pass through, nobody leaves,” one indigenous miner lamented.

This collaboration contradicts claims by Caracas of distancing itself from Colombian rebels. Evidence suggests Venezuelan state forces actively work alongside guerrilla organizations, even appearing together in public meetings and sharing vehicles. Cross-border cooperation extends to Colombian officials who facilitate the smuggling of mined materials for personal gain.

The extracted minerals are transported through a complex network, often across the Orinoco River to Colombia, where they are fraudulently documented and shipped to China. Investigators have identified collection points where Venezuelan ores are assayed, then falsely declared as less valuable metals, or even disguised as originating from Colombia itself.

More recently, Venezuelan ores are being smelted in Colombia, producing ingots containing tin and rare earth metals that are flown directly to China. This trade is enabled by Colombia’s lax regulations and inadequate enforcement, with seized cargos often returned to traders due to a lack of clarity regarding legal violations.

“Colombia’s state agencies are hopelessly behind organized crime in the critical minerals business, and corruption is pervasive,” one investigator stated. “But the problem isn’t just corruption; it’s bureaucratic paralysis and a complete lack of adequate legal frameworks to address illegal extraction and trade.”

The core of the problem lies in the absence of effective state presence in the Orinoco and Amazon river basins. This void has allowed criminal enterprises to flourish, creating a situation where reclaiming control over vast territories seems almost impossible. The guerrillas I encountered were better equipped and more confident than their counterparts in the Venezuelan national guard.

The immense profits generated by mining, backed by well-funded mercenary armies, suggest this crisis is far from over. Solutions lie in improving detection methods, controlling the flow of metals, and strengthening regulations at both extraction and export levels. Accurate assays and community control over mining operations are crucial.

“Right now, miners are stripping topsoil just to see what rocks lie beneath, causing unnecessary environmental damage. They don’t even know what they’ve got,” one expert observed. Following the money and identifying the companies profiting from this misery is also essential.

The ultimate irony is that this devastation is driven by the global demand for “green” technologies – wind turbines, electric vehicles, and solar panels. The extraction of critical minerals needed for these advancements is destroying indigenous communities and vital ecosystems, while simultaneously fueling guerrilla violence.