In September 1859, telegraph operators experienced a terrifying anomaly. As they tapped out messages across vast distances, a brilliant, otherworldly aurora illuminated the sky, stretching from the tropics to the poles. Then came the shock – literal sparks showering from their equipment, jolting them from their seats and igniting papers.

These weren’t random malfunctions. Operators discovered they could still send messages even with batteries disconnected, unknowingly channeling the immense energy of the most powerful geomagnetic storm in recorded history. This event, triggered by a colossal solar flare observed by Richard Carrington, unleashed a surge of energy that electrified the telegraph wires themselves.

Imagine the bewilderment of those 19th-century operators contemplating today’s complex technology. Our modern world, utterly reliant on electricity, is far more vulnerable to the sun’s fury than they could have ever imagined.

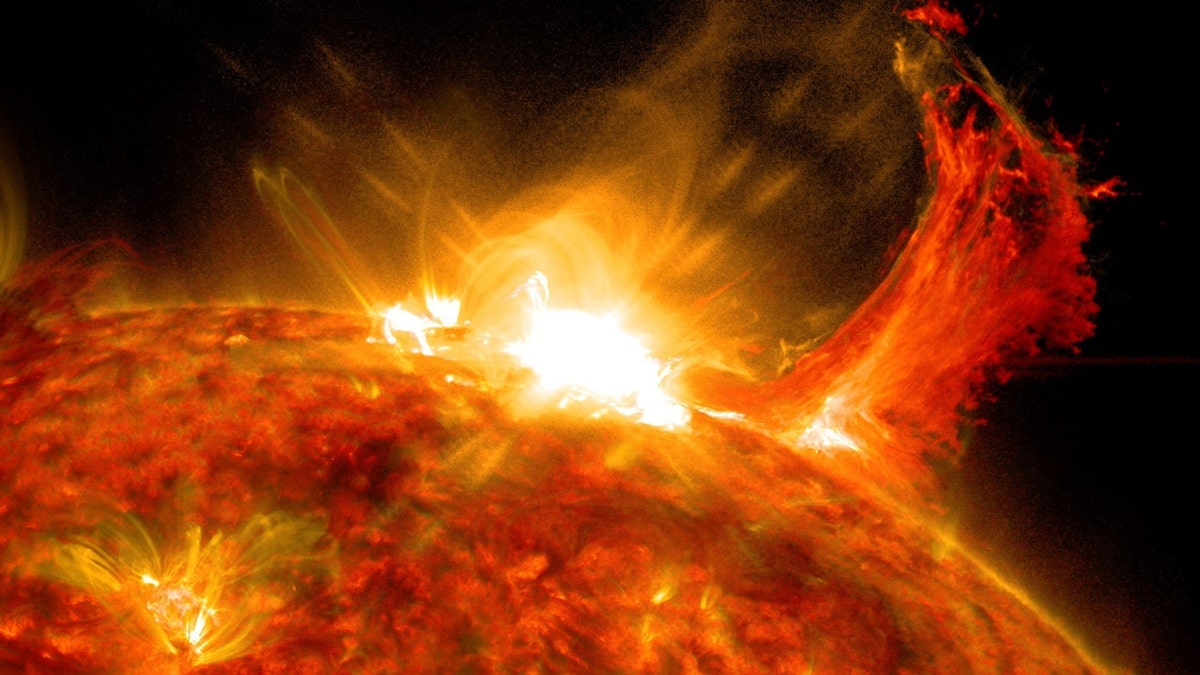

The sun operates on an approximately 11-year cycle, and we are currently approaching its peak. Recently, a massive sunspot, AR4366, rapidly grew to nearly half the size of the one responsible for the Carrington Event. On February 1st, it unleashed an X8-class solar flare – the most powerful of the current cycle.

In the 24 hours prior, this unstable region bombarded Earth with 23 M-class and four X-class flares. The resulting extreme ultraviolet radiation disrupted shortwave radio communications across the South Pacific for hours. But the real threat lies in what could follow: a coronal mass ejection (CME).

This explosion ejected a dense cloud of plasma potentially aimed at Earth. If it arrives with sufficient force, it will compress our planet’s magnetic field, inducing powerful geomagnetically induced currents (GICs) – essentially electrifying the Earth’s surface. These currents can surge through our high-voltage transmission lines, the very backbone of our electric grid.

A Carrington-level event today wouldn’t be a mere inconvenience. It could melt or destroy hundreds of massive transformers, triggering widespread blackouts lasting months, even years. Supply chains would crumble, essential services would fail, and the economic damage in the United States alone could range from $600 billion to $2.6 trillion, with devastating loss of life.

Despite these clear warnings, America’s power grid remains dangerously exposed. Existing vulnerability assessments, often based on decades-old European research from a period of unusually low solar activity, dramatically underestimate the risk. They fail to account for our increasingly interconnected grid and the sun’s current, heightened activity.

The situation is further complicated by our reliance on foreign manufacturers. Most large power transformers are now made in China, South Korea, and Germany, with lead times stretching to four years or more even under normal circumstances. Replacing damaged transformers after a major event could take a decade – time we simply wouldn’t have.

Fortunately, a solution exists. Neutral Blocking Devices, equipped with capacitors, can be installed in transformers to prevent catastrophic damage. These devices block harmful currents induced by solar storms or electromagnetic pulses, while allowing normal power flow. They also extend transformer lifespan and reduce energy losses.

The cost of protecting the most vulnerable 6,000 transformers nationwide is estimated at around $4 billion – a tiny fraction of the potential trillions in damages. Yet, utilities and regulators hesitate, reluctant to pass even modest costs onto consumers or update outdated standards.

Congress and state legislatures must act decisively, mandating or incentivizing the installation of these protective devices. Utilities must prioritize grid resilience, and regulators must base their decisions on current risks, not outdated assumptions. The Carrington Event shocked telegraph operators; a repeat could plunge an entire civilization into a pre-industrial dark age.

We possess the technology to prevent this catastrophe. The question is, will we act before it’s too late?