A mother’s desperate plea arrived in 1940s Canada: her teenage son, once caught stealing, had been transformed. Not by punishment, but by a comic book. She wrote of a changed boy, returning a lost purse brimming with money, a testament to the power of cautionary tales printed in vivid color.

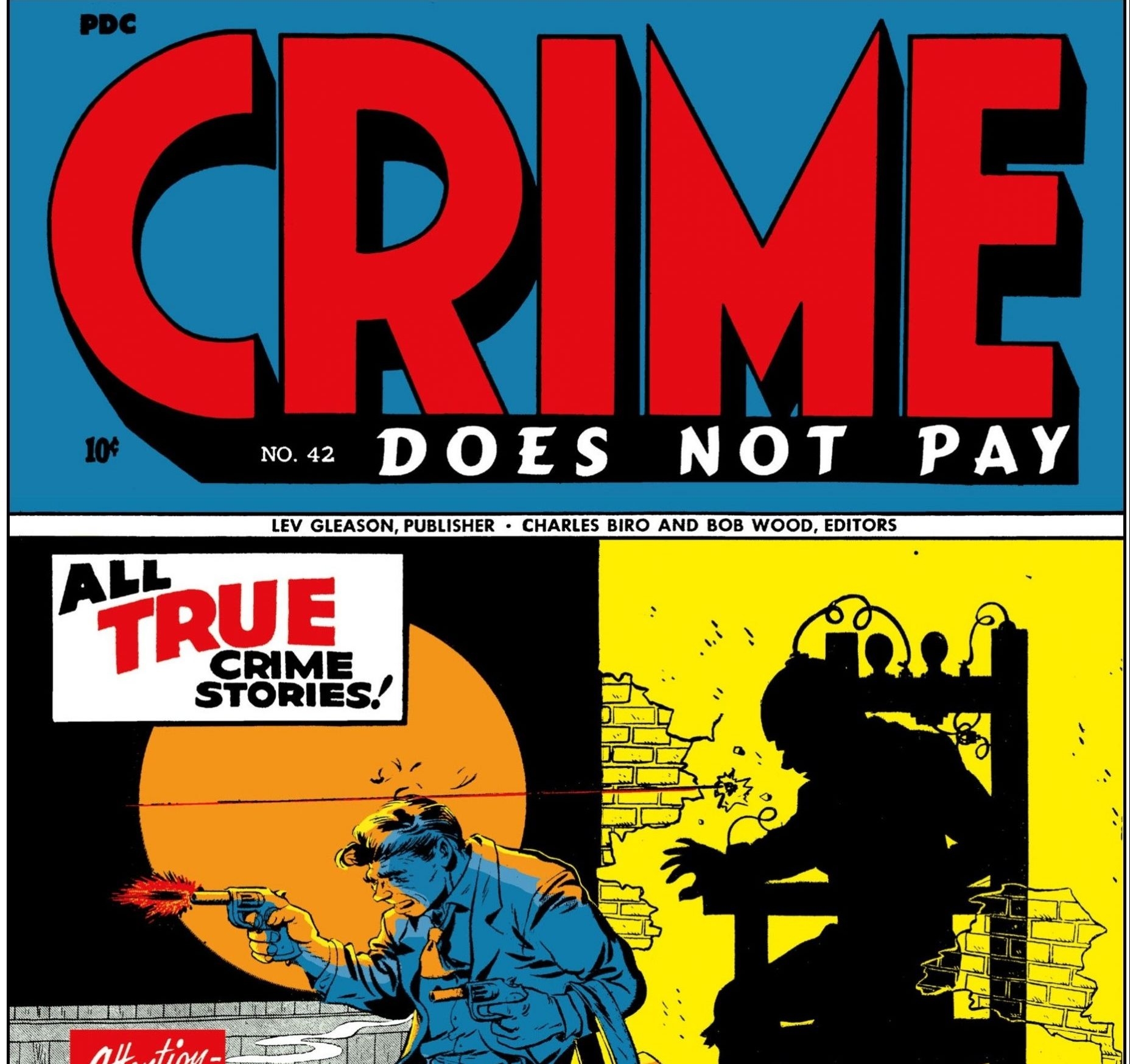

That comic wasCrime Does Not Pay, a sensation that gripped a generation. At its peak, six million copies flew off newsstands each month, delivering shocking stories ripped from the headlines. Each issue promised a grim finale – the electric chair, a hail of police bullets – a stark warning against a life of crime.

The comic’s success stemmed from an unlikely partnership. Charlie Biro, a recognized genius, and Bob Wood, his quieter, less celebrated counterpart. Both men shared a love for fast living, for women and strong drink, but they were guided by a remarkably generous publisher, Lev Gleason, who believed in sharing the wealth with his creators.

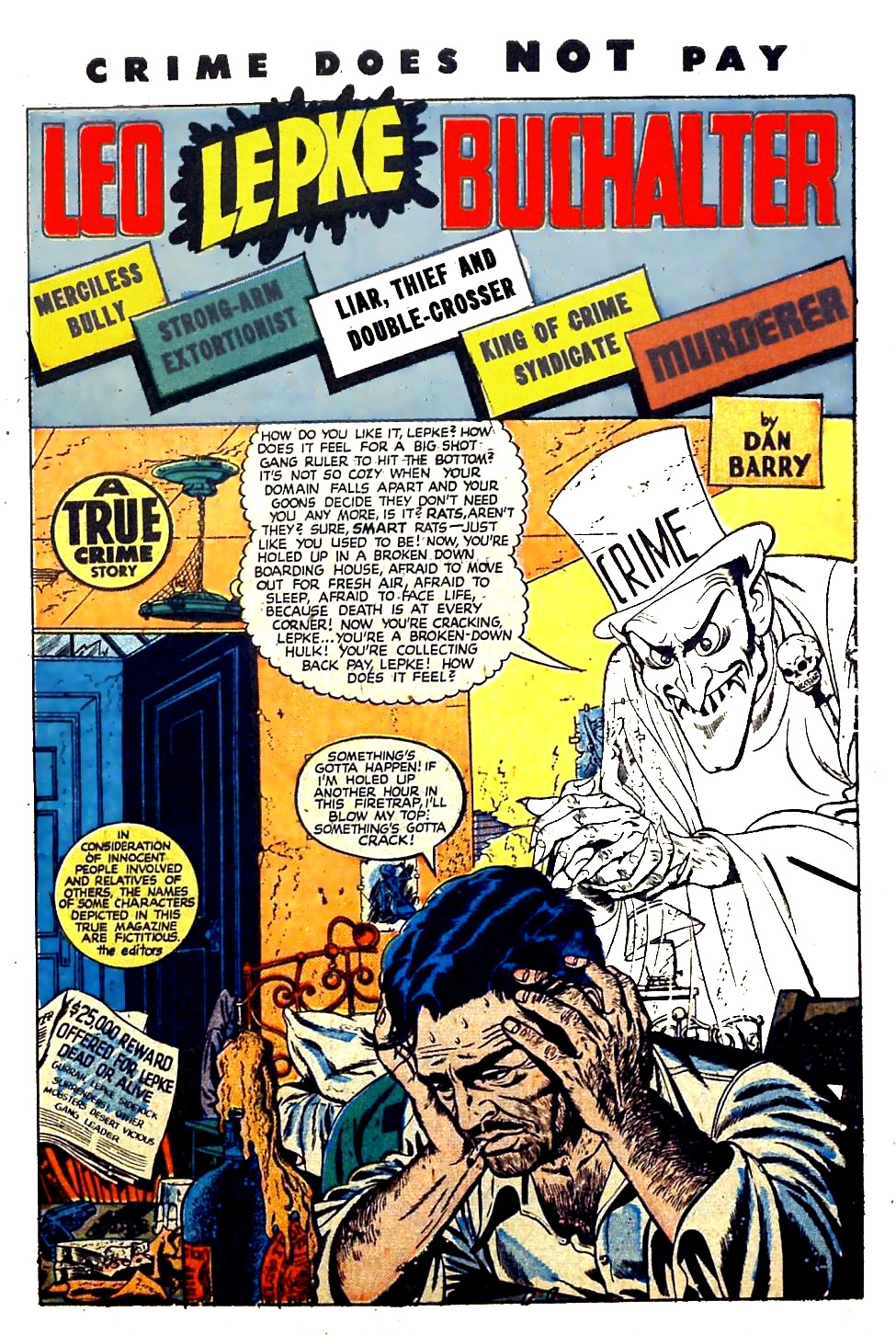

Launched in 1942,Crime Does Not Paydidn’t shy away from the dark side. It featured notorious criminals like Baby Face Nelson and Machine Gun Kelly, narrated by the chillingly named Mr. Crime. Sales soared, fueled by a readership drawn to the gritty realism and the forbidden allure of a world filled with violence, drugs, and illicit affairs.

The creators themselves lived lavishly, Gleason observing they “spent the money faster than they made it.” They even maintained a discreet love shack, catering to the affections of devoted female fans. But beneath the success, trouble was brewing.

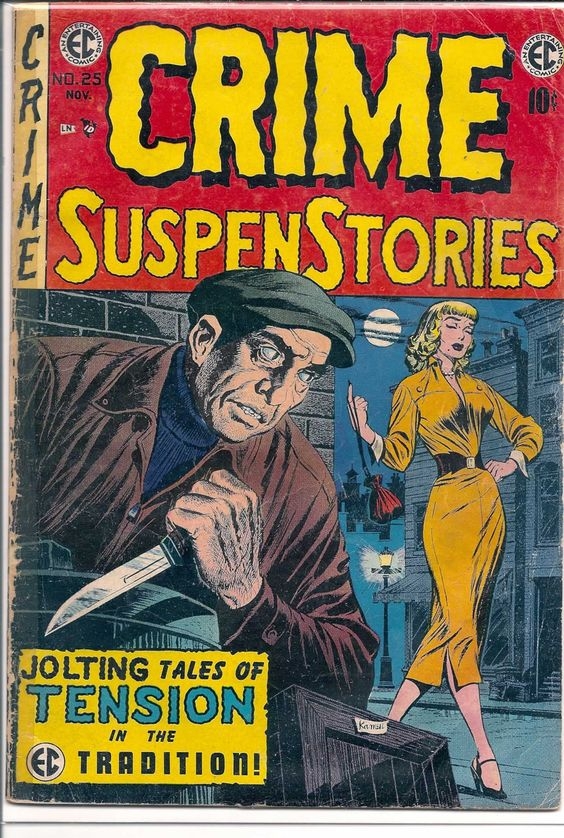

By the late 1950s, a moral panic erupted. Dr. Fredric Wertham launched a crusade against comics, blaming them for juvenile delinquency and illiteracy. The result was the restrictive Comics Code Authority, effectively silencingCrime Does Not Paywith its 147th issue. Canada, ever cautious, had banned such publications even earlier, in 1949.

Biro transitioned to graphic art for NBC, but Wood’s fate took a darker turn. He descended into deeper alcoholism, finding work creating cartoons for exploitative, soft-core publications. His life spiraled towards a horrifying climax on August 27, 1958.

A taxi driver picked up a disheveled and agitated Wood in a wealthy neighborhood. Wood confessed, chillingly, to murder. He claimed he’d killed a woman in Room 91 of the Irving Hotel, offering the driver a bribe to alert the newspapers. He intended to end his life in the river.

Police discovered the scene: an Irving Hotel room littered with liquor bottles, and the body of Violette Phillips, a 45-year-old divorcee, lying in a blood-soaked negligee. Phillips had left her husband for Wood, and their eleven-day binge had ended in a brutal argument.

The irony was devastating. One of the creators ofCrime Does Not Pay, a comic dedicated to the consequences of criminal acts, was arrested for a real-life, violent crime. His life had become a twisted echo of the stories he helped create.

Wood pleaded guilty to manslaughter and spent three years in Sing Sing prison. Upon his release in 1963, his career was shattered. He found work as a dishwasher in a New Jersey diner, a stark contrast to his former success.

His troubles didn’t end there. Rumors circulated about gambling debts and connections to dangerous individuals within the prison system. Then, in November 1966, Bob Wood was found dead on the New Jersey Turnpike. Was it an accident, or a calculated act of retribution? The truth remains shrouded in mystery.

The story of Bob Wood serves as a grim reminder: crime, in the end, truly does not pay. It’s a cautionary tale far more potent than any printed in the pages of a ten-cent comic book.