Charlotte LaRoy possessed a singular fascination, born in the 1940s amidst a world of everyday objects. It wasn’t dolls or games that captured her attention, but something far more unexpected: paper napkins.

She noticed everything about them – their vibrant colours, unique shapes, and the subtle textures that distinguished each one. Beyond aesthetics, she appreciated their simple, practical purpose, a quiet observation that would blossom into a lifelong passion.

Over decades, this fascination quietly grew into an extraordinary collection, carefully tucked away in a blanket box under her bed. It wasn’t a deliberate pursuit of value, but a gentle accumulation of moments, each napkin a small, tangible memory.

Finally, LaRoy brought her trove – over 1,100 napkins in all – to the Library of Virginia. The curators were astonished, welcoming her collection into their care alongside historical documents and ancient texts.

The collection isn’t merely a display of disposable items; it’s a vibrant reflection of American life, spanning decades of social change and offering an intimate glimpse into the world through one woman’s eyes.

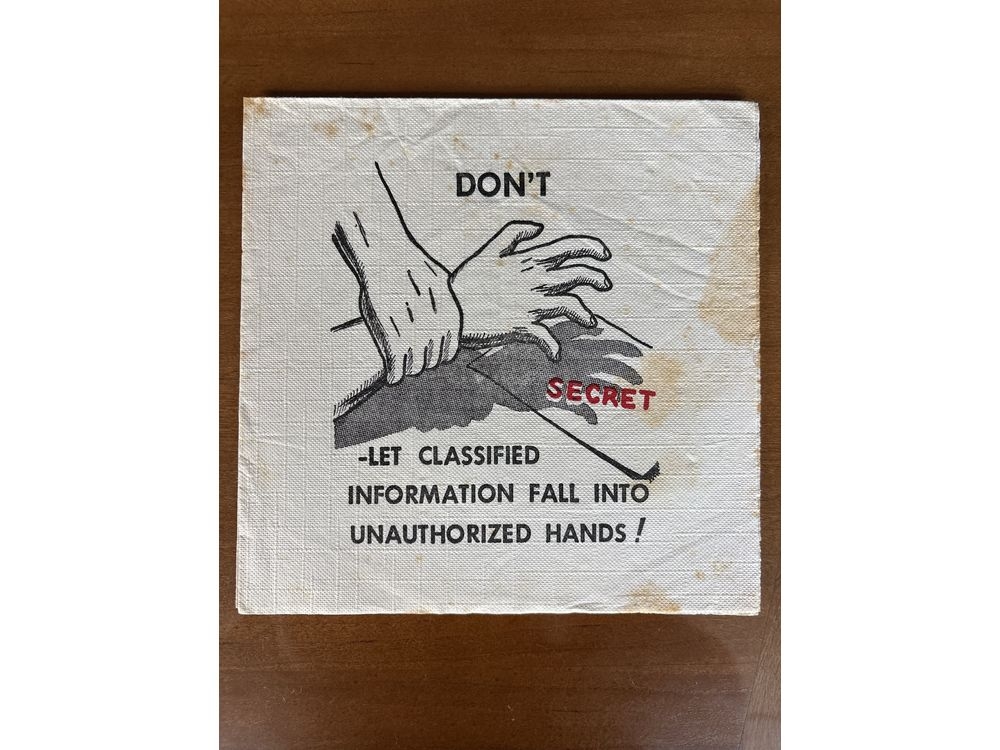

Among the napkins are stark warnings from the Pentagon, relics of the Red Scare era, featuring cartoonish imagery and blunt messages like, “Keep classified information to yourself, pardner!” They speak to a time of paranoia and political tension.

A surprising number originated from bars, revealing a glimpse into a more casual, often problematic past. One napkin, featuring a woman at a washboard, boldly proclaimed, “The Ideal Wife,” a sentiment jarringly out of step with modern values.

But the collection isn’t solely defined by its darker edges. Jolly Christmas scenes, advertisements for vanished airlines, and even lyrics from country songs add layers of nostalgia and charm.

Intricate “Map-kins” unfolded to reveal whimsical road trip destinations, like a peculiar castle in Death Valley and the aptly named Duckwater Peak in Nevada, complete with a playful “Quack! Quack!”

Political moments are also captured within the collection, from an inauguration napkin for Virginia’s governor A. Linwood Holton Jr. in 1970 to a celebration of L. Douglas Wilder’s historic election as the first African American U.S. governor.

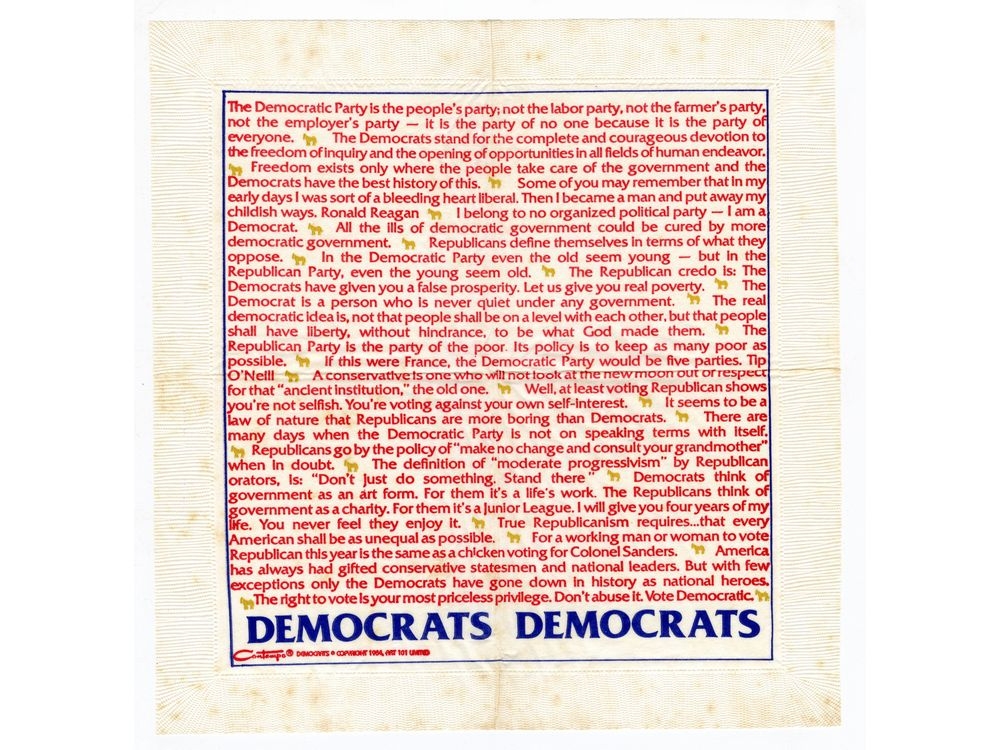

In 1984, the presidential race between Ronald Reagan and Walter Mondale was playfully dissected on a pair of duelling napkins, each printed in red and blue, offering sharp political commentary in bite-sized aphorisms.

One napkin quipped, “Republicans study the financial pages of the newspaper. Democrats put them on the bottom of the bird cage,” while the other retorted, “For a working man or woman to vote Republican this year is the same as a chicken voting for Colonel Sanders.”

When Dale Neighbours, the visual studies collection coordinator at the Library of Virginia, first learned of the collection, he wondered about the person who dedicated years to preserving such seemingly insignificant items.

“I don’t know what to do with them anymore,” LaRoy had confessed, a hint of relief in her voice. She had amassed a unique archive, but felt it was time to share it with a wider audience.

Neighbours understood the power of “ephemera” – the everyday objects that often reveal the most about a particular time and place. He had even used similar items to ensure historical accuracy in Martin Scorsese films.

He was particularly drawn to the mid-century designs and the Pentagon napkins, recognizing their potential to captivate future researchers. He was deeply moved by LaRoy’s desire to see her collection appreciated.

Years later, when contacted about her collection, LaRoy responded with a joyous laugh, surprised and delighted that her quirky passion was garnering attention. She had always been a private person, content to nurture her creative hobbies quietly.

Alongside the napkins, she created “Miscommunication Baskets” – colourful sculptures woven from old computer cords and phone parts, a testament to her artistic spirit. She rarely displayed the napkin collection, except to politely request one when needed.

Her collecting rule was simple: napkins had to be unused, and she avoided duplicates. Some were gifts from colleagues of her parents, who worked for the government. Her father was a leading expert in food safety, and her mother an analyst at the Pentagon.

Family road trips and milestone events provided a steady stream of new discoveries, each napkin becoming a small piece of their shared history. They were a tangible reminder of cherished memories.

Now, facing memory challenges, LaRoy recognizes the poignant value of these keepsakes, especially given her father’s struggle with Alzheimer’s. They offer a connection to the past, a way to revisit moments that might otherwise fade.

Sitting with her husband, Bernard, she revisited digitized images of her collection, giggling at a golf-themed Pentagon warning and a cocktail napkin featuring a provocative image and the phrase, “Girls with curves are usually surrounded by men with angles.”

While many details had become hazy, one napkin instantly sparked a vivid memory: a wedding napkin with intertwined blue hearts, embossed with the names “Stacey & Andrew” and the date “November 6, 2010.”

“Yeah,” she said, her voice trembling with recognition. “That’s our son.” In that moment, a simple paper napkin transcended its humble origins, becoming a powerful symbol of love, family, and enduring memory.