The snow-dusted forest service road held a hidden terror. Sean Boxall and his beloved husky, Moon, had driven west from Radium Hot Springs, seeking a peaceful day of skiing. Moon, a rescued companion, bounded from the car, eager to explore the crisp winter air, unaware of the danger lurking just off the road.

A barely visible sign, obscured by branches, hinted at the presence of a trapline. Before Sean could react, a flash of movement – Moon, drawn by an unseen scent, triggered a freshly baited trap. The sound that followed wasn’t a snap, but a sickening crunch that shattered the tranquility of the mountains.

It wasn’t immediate. The trap, a brutal instrument of steel jaws, hadn’t killed Moon instantly. Instead, it crushed his throat, and he thrashed in agonizing terror, a desperate struggle against an invisible force. Sean, heart pounding, raced to his dog, frantically trying to pry apart the mechanism, his hands raw against the unforgiving metal.

Moon looked at him, eyes pleading, and bit Sean’s hand – a desperate attempt to communicate his suffering. Blood mingled with snow as Sean fought against the trap, fueled by a primal need to save his friend. Every failed attempt, every torn muscle, was a testament to his love and helplessness.

Finally, Sean retrieved a chainsaw from his truck, a desperate measure in a desperate situation. But it was too late. When the trap finally released its grip, Moon was gone, his final moments filled with unimaginable pain on land considered safe and legal for this practice.

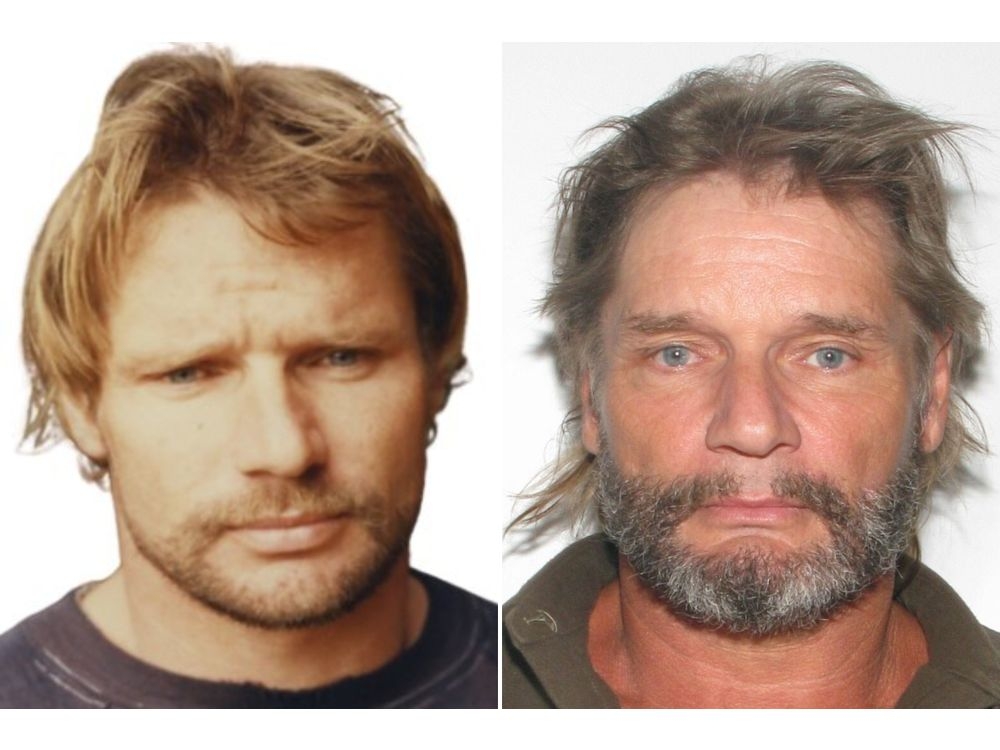

Sean’s partner, Nicole Trigg, is now channeling her grief into action. Alongside the animal rights group The Fur-Bearers, she’s spearheading a campaign to reform trapping regulations in British Columbia, a province where these devices can be set with alarming proximity to public roads and minimal warning.

The current rules offer little protection. There are no restrictions on how close traps can be placed to roads, and signage is often inadequate. Trigg’s campaign, “Moon’s Law,” has already generated thousands of letters to the Minister of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship, demanding change.

This isn’t an isolated incident. Dozens of companion animals fall victim to traps in Canada each year, caught in a system that prioritizes a traditional practice over the safety of beloved pets and the ethical treatment of wildlife. The Conservation Officer Service confirmed the trapper was operating legally, a chilling acknowledgement of the existing framework.

Licensed trappers in B.C. are permitted to kill seventeen species of fur-bearing animals, and the industry is supported by government subsidies. While the B.C. Trappers Association maintains that body-gripping traps are designed for swift, humane action on target species, they acknowledge the risk to non-target animals like Moon.

The association emphasizes the importance of public awareness and responsible land use, urging dog owners to keep their animals leashed. But for Sean and Nicole, that’s a hollow consolation. Their loss serves as a stark reminder of the hidden dangers lurking in the wilderness and the urgent need for a more compassionate and regulated approach to trapping.

Moon’s story is a plea for change, a demand that our public lands be truly safe for all who venture into them, and a testament to the enduring bond between a man and his dog.